Routine activities theory is a theory of crime events. This differs from a majority of criminological theories, which focus on explaining why some people commit crimes—that is, the motivation to commit crime— rather than how criminal events are produced. Although at first glance this distinction may appear inconsequential, it has important implications for the research and prevention of crime. Routine activities theory suggests that the organization of routine activities in society create opportunities for crime.

Outline

I. Introduction

II. Theory

III. Methods

IV. Complementary Theories, Perspectives, and Applications

V. Future Directions

VI. Conclusion

I. Introduction

Routine activities theory is a theory of crime events. This differs from a majority of criminological theories, which focus on explaining why some people commit crimes—that is, the motivation to commit crime— rather than how criminal events are produced. Although at first glance this distinction may appear inconsequential, it has important implications for the research and prevention of crime.

Routine activities theory suggests that the organization of routine activities in society create opportunities for crime. In other words, the daily routine activities of people—including where they work, the routes they travel to and from school, the groups with whom the socialize, the shops they frequent, and so forth—strongly influence when, where, and to whom crime occurs.

These routines can make crime easy and low risk, or difficult and risky.  Because opportunities vary over time, space, and among people, so too does the likelihood of crime. Therefore, research that stems from routine activities theory generally examines various opportunity structures that facilitate crime; prevention strategies that are informed by routine activities theory attempt to alter these opportunity structures to prevent criminal events.

Because opportunities vary over time, space, and among people, so too does the likelihood of crime. Therefore, research that stems from routine activities theory generally examines various opportunity structures that facilitate crime; prevention strategies that are informed by routine activities theory attempt to alter these opportunity structures to prevent criminal events.

Routine activities theory was initially used to explain changes in crime trends over time. It has been increasingly used much more broadly to understand and prevent crime problems. Researchers have used various methods to test hypotheses derived from the theory. Since its inception, the theory has become closely aligned with a set of theories and perspectives known as environmental criminology, which focuses on the importance of opportunity in determining the distribution of crime across time and space.

Environmental criminology, and routine activities theory in particular, has very practical implications for prevention; therefore, practitioners have applied routine activities theory to inform police practices and prevention strategies. This research paper contains a review of the evolution of routine activities theory; a summary of research informed by the theory; complementary perspectives and current applications; and future directions for theory, research, and prevention.

II. Theory

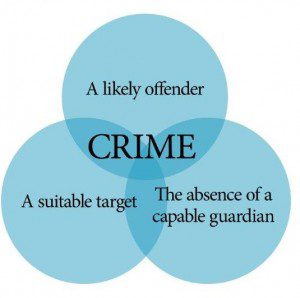

In 1979, Cohen and Felson questioned why urban crime rates increased during the 1960s, when the factors commonly thought to cause violent crime, such as poor economic conditions, had generally improved during this time. Cohen and Felson (1979) suggested that a crime should be thought of as an event that occurs at a specific location and time and involves specific people and/or objects. They argued that crime events required three minimal elements to converge in time and space: (1) an offender who was prepared to commit the offense; (2) a suitable target, such as a human victim to be assaulted or a piece of property to be stolen; and (3) the absence of a guardian capable of preventing the crime. The lack of any of these three elements, they argued, would be sufficient to prevent a crime event from occurring. Drawing from human ecological theories, Cohen and Felson suggested that structural changes in societal routine activity patterns can influence crime rates by affecting the likelihood of the convergence in time and space of these three necessary elements. As the routine activities of people change, the likelihood of targets converging in time and space with motivated offenders without guardians also changes. In other words, opportunities for crime—and, in turn, crime patterns—are a function of the routine activity patterns in society.

Cohen and Felson (1979) argued that crime rates increased after World War II because the routine activities of society had begun to shift away from the home, thus increasing the likelihood that motivated offenders would converge in time and space with suitable targets in the absence of capable guardianship. Routine activities that take place at or near the home tend to be associated with more guardianship—for both the individual and his or her property—and a lower risk of encountering potential offenders. When people perform routine activities away from the home, they are more likely to encounter potential offenders in the absence of guardians. Furthermore, their belongings in their home are left unguarded, thus creating more opportunities for crime to take place.

One of the greatest contributions of routine activities theory is the idea that criminal opportunities are not spread evenly throughout society; neither are they infinite. Instead, there is some limit on the number of available targets viewed as attractive/suitable by the offender. Cohen and Felson (1979) suggested that suitability is a function of at least four qualities of the target: Value, Inertia, Visibility, and Access, or VIVA. All else being equal, those persons or products that are repeatedly targeted will have the following qualities: perceived value by the offender, either material or symbolic; size and weight that makes the illegal treatment possible; physically visible to potential offenders; and accessible to offenders. Cohen and Felson argued that two additional societal trends—the increase in sales of consumer goods and the design of small durable products—were affecting the crime by means of the supply of suitable targets. These trends in society increased the supply of suitable targets available and, in turn, the likelihood of crime. As the supply of small durable goods continued to rise, the level of suitable targets also rose, thus increasing the number of available criminal opportunities.

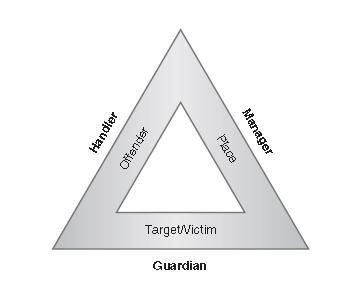

Since its inception, routine activities theory has been developed to further specify the necessary elements for a criminal event and those that have the potential to prevent it. The people who prevent crime have been subdivided according to whom or what they are supervising—offender, target, or place—and are now collectively referred to as controllers. Handlers are people who exert informal social control over potential offenders to prevent them from committing crimes (Felson, 1986). Examples of handlers include parents who chaperone their teenager’s social gatherings, a probation officer who supervises probationers, and a school resource officer who keeps an eye on school bullies. Handlers have some sort of personal connection with the potential offenders. Their principal interest is in keeping the potential offender out of trouble. Guardians protect suitable targets from offenders (Cohen & Felson, 1979). Examples of guardians include the owner of a car who locks his vehicle, a child care provider who keeps close watch over the children in public, and a coworker who walks another to his car in the parking garage. The principal interest of guardians is the protection of their potential targets. Finally, managers supervise and monitor specific places (Eck, 1994). Place managers might include the owner of a shop who installs surveillance cameras, an apartment landlord who updates the locks on the doors, and park rangers who enforce littering codes. The principal interest of managers is the functioning of places. Eck (2003) depicted this more comprehensive version of routine activities theory was as a crime triangle (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The Crime Triangle

The inner triangle represents the necessary elements for a crime to occur: A motivated offender and suitable target must be at the same place at the same time. The outer triangle represents the potential controllers—guardians, handlers, and managers—who must be absent or ineffective for a crime to occur; the presence of one effective controller can prevent the criminal event.

Controllers have been described in greater detail. Felson (1995) indicated who is most likely to successfully control crime as a guardian, handler, or manager. He asserted that individuals’ tendency to discourage crime—by supervising targets, offenders, or places—varies with degree of responsibility. He described four varying degrees of responsibility:

- Personal, such as owners, family, and friends

- Assigned, such as employees with a specific assigned responsibility

- Diffuse, such as employees with a general assigned responsibility

- General, such as strangers and other citizens

Controllers who are more closely associated with potential offenders, targets, or places, are more likely to successfully take control and prevent crime. As responsibility moves from personal to general, the likelihood that crime will be prevented diminishes. For example, a shop owner will be much more likely to take control and prevent shoplifting in her store compared with a stranger who infrequently comes to the store. Residents will be more likely to prevent crime on their own street block, rather than on the blocks they travel to and from work.

The characteristics of a suitable target have been expanded and applied to products that are frequently targeted for theft. Clarke (1999) extended Cohen and Felson’s (1979) work on target suitability to explain the phenomenon of “hot products.” Clarke suggested that relatively few hot products account for a large proportion of all thefts. He argues there are six key attributes of hot products that increase the likelihood that they will be targeted by thieves. Specifically, crime is concentrated on products that are CRAVED, that is, Concealable, Removable, Available, Valuable, Enjoyable, and Disposable (Clarke, 1999).

To summarize, routine activities theory is a theory of crime events. Routine activities theory differs from other criminological theories in a fundamental way. Before the advent of routine activities theory, nearly all criminological theory had focused solely on factors that motivate offenders to behave criminally, such as biological, sociological, and economic conditions that might drive individuals to commit crimes. Conversely, routine activities theory focuses on a range of factors that intersect in time and space to produce criminal opportunities and, in turn, criminal events. Although standard criminological theories do not explain how crimes happen to occur at some places (but not others), at some times (but not others), and to some targets (but not others), routine activities theory does not explain why some people commit crimes and others do not. It is important to note that routine activities theory suggests that crime can increase and decline without any change in the number of criminals. Instead, there might be an increase in the availability of suitable targets, a decline in the availability or effectiveness of controllers, or a shift in the routine activities of society that increase the likelihood that these elements will converge in time and space. This notion that the offender is but one contributor to the crime event has both theoretical and practical implications. First, it insinuates that theories that focus only on offender factors are not sufficient to explain crime patterns and trends, only the supply of motivated offenders. Second, it suggests a much broader range of prevention possibilities. Whereas other criminological theories suggest changes to the social, economic, and political institutions of society to alter the factors that motivate people to commit crimes, routine activities theory indicates that shifts in the availability of suitable targets; the characteristics of places; and the presence of capable guardians, place managers, or handlers can produce immediate reductions in crime. Furthermore, changes in the routine activity patterns of society that affect the likelihood that these elements will converge in space and time can also prevent crime events without directly affecting the supply of motivated offenders. Given these policy implications, researchers have derived various testable hypotheses from routine activities theory to explore its validity.

III. Methods

Routine activities theory has guided research designed to understand a range of phenomena, including crime trends over time, distributions of crime across space, and individual differences in victimization. In addition, researchers have considered how opportunities for crime might exist at multiple levels. For example, the characteristics of one’s neighborhood and the features of the home might influence the likelihood of burglary victimization. Researchers have used various research methods to meet these different needs. The selection of research reviewed in the following paragraphs illustrates the different methods researchers have used to test hypotheses developed from routine activities theory.

A. Using Routine Activity to Predict Crime Trends

Routine activities theory was first used to understand changes in crime trends over time. To do this, researchers examine how crime rates fluctuate over time with changes in macrolevel routine activity trends to determine whether changes in routine activities are associated with changes in crime trends. If they are, this indicates support for the theory. In their initial presentation of the theory, Cohen and Felson (1979) pointed to a shift in the structural routine activities of society to explain why urban crime rates increased during the 1960s, when the factors thought to cause violent crime, such as economic conditions, had generally improved during this time period. They argued that the dispersion in activities away from the family and household caused an increase in target suitability and a decrease in guardianship. In other words, people were leaving their households unoccupied and unguarded more frequently, as well as exposing themselves as targets to potential motivated offenders. To test this hypothesis, Cohen and Felson developed a household activity ratio to measure the extent to which households were left unattended. 1 They predicted that changes in the dispersion of activities away from the family and household explained crime rates over time, arguing that non-household activities increase the probability that motivated offenders will converge in time and space in the absence of capable guardians. Using a time series analysis, they found that the household activity ratio was significantly related to burglary, forcible rape, aggravated assault, robbery, and homicide rates from 1947 to 1974 (Cohen & Felson, 1979). Consistent with Cohen and Felson’s initial study, subsequent macrolevel studies have demonstrated that variations in society’s structural organization of routine activities are related to variations in crime trends over time (Felson & Cohen, 1980). In other words, research has generally shown that routine activities that take people away from their home tend to be associated with increases in crime rates.

B. Using Routine Activities to Predict the Distribution of Crime Across Space

Routine activities theory has also been used to explain distributions of crime across space. Unlike the research just reviewed, which examined how crime rates changed in the same place over time (i.e., the United States from year to year), this type of research examines how crime rates differ across various places at the same time (i.e., different cities in the United States during a given year). Researchers have used routine activities theory to develop testable hypotheses about why some areas have higher crime rates than others. To do this, they examine whether the routine activities of people living in places with higher levels of crime differ from the routine activities of people living in places with lower levels of crime. For example, Messner and Blau (1987) hypothesized that routine leisure activities that take place in the household will result in lower crime rates, whereas those that take people away from their households will result in higher crime rates. To test these hypotheses, they used data from the 124 largest Standard Metropolitan Statistical Areas in the United States during the time period around 1980. Specifically, they hypothesized that higher levels of aggregate television viewing would be associated with lower city crime rates, because routine leisure activities that take place in the household provide potential targets with a greater level of guardianship. Conversely, they hypothesized that a greater supply of sports and entertainment establishments will be associated with higher city crime rates, because leisure activities that remove people from their homes leave suitable targets unguarded. In general, their analyses support these hypotheses. Higher levels of television viewing were associated with lower rates of forcible rape, robbery, aggravated assault, burglary, larceny, and auto theft. Conversely, a greater supply of sports and entertainment establishments was associated with higher rates of murder and non-negligent manslaughter, forcible rape, robbery, aggravated assault, burglary, and larceny.

C. Using Routine Activities to Predict Differences in Victimization

Routine activities theory has also been used to explain differences in victimization across individuals. Although Cohen and Felson (1979) initially used the theory to explain national-level crime trends, the mechanisms described by the theory are actually microlevel in nature: A victim comes into contact with an offender in the absence of any capable controllers. This has led many researchers to use individual-level victimization data to understand differences in victimization risk given the routine activities of the potential victim. Specifically, researchers compare the routine activities of victims to those of non-victims to understand the effect of lifestyle and routine activities on the likelihood of victimization. Victimization survey data have become increasingly available in recent decades, making such methodology more common. Therefore, researchers have examined how the routine activities of individuals affect their likelihood of various forms of victimization, including property crime (Mustaine & Tewksbury, 1998), violent crime (Sampson, 1987), and stalking (Fisher, Cullen, & Turner, 2002)

Miethe, Stafford, and Long (1987) argued that the routine activities of individuals differentially place some people and/or their property in the proximity of motivated offenders, thus leaving them vulnerable to victimization. Using victimization data from the 1975 National Crime Survey, Miethe et al. explored whether individuals’ major daily activities and frequency of nighttime activities affected their likelihood of property and violent victimization. Their analyses indicated that individuals who performed their major daily activities outside of the home had relatively higher risks of property victimization compared with those whose daily activities kept them at home. The location of major daily activities, however, was not significantly related to the risk of violent victimization. In terms of the frequency of nighttime activities, Miethe et al. found that individuals with a high frequency of nighttime activities were at an increased risk for property and violent victimization.

D. Routine Activities and Multilevel Opportunity

At first, researchers examined macro- and microlevel hypotheses derived from routine activities separately. Macrolevel routine activities have been used to explain crime rates, and the routine activities of individuals have been used to explain victimization risk. In more recent years, researchers have begun to explore whether opportunity factors operate at both individual and neighborhood levels to impact victimization risk (e.g., Sampson & Wooldredge, 1987; Wilcox Rountree, Land, & Miethe, 1994). In other words, do the routine activities of the neighborhood in which an individual resides independently influence his victimization risk beyond the effect of his own characteristics and routine activities that leave him vulnerable to crime? For example, leaving one’s door unlocked might contribute to victimization risk; living in a neighborhood where it is common to leave one’s door unlocked might also contribute to victimization risk. In the first case, one’s house can be easily entered if a burglar should try to enter. In the second case, a burglar knows to try to enter the home given the neighborhood norm of leaving doors unlocked. These two factors may both contribute to the risk of victimization for this individual.

In addition, researchers have questioned whether the effects of individual routine activities on victimization risk vary by neighborhood. For example, does leaving one’s door unlocked increase risk for burglary victimization to a particular level, regardless of whether one lives in the suburbs or in the city, or do the neighborhood characteristics condition the effect of individual routine activities on victimization risk? Routine activities theory and these types of research questions have inspired further theoretical developments in the area of multilevel opportunity (Wilcox, Land, & Hunt, 2003).

To answer these questions, researchers use data on both the characteristics of the neighborhood that indicate opportunities for crime, as well as the routine activities and other characteristics of the victim that might put him at risk for victimization. To analyze such data, researchers rely on sophisticated multilevel modeling techniques that allow them to determine the effects of individual- and neighborhood-level factors at the same time, as well as the extent to which neighborhood characteristics might condition the effects of individual routine activities on victimization risk.

IV. Complementary Theories, Perspectives, and Applications

Routine activities theory is closely linked to and shares similar assumptions with several other theories and perspectives that are collectively referred to as environmental criminology. Unlike traditional criminology, environmental criminology has focused primarily on the proximate environmental and situational factors that facilitate or prevent criminal events. While not discounting individual differences in motivation to commit crime, the primary focus of this area of theory and research has been on understanding the opportunity structures that produce temporal and spatial patterns of crime. In addition to routine activities theory, environmental criminology encompasses the rational choice perspective (e.g., Clarke & Cornish, 1985), situational crime prevention (Cornish & Clarke, 2003), and crime pattern theory (P. J. Brantingham & Brantingham, 1981, 1993; P. L. Brantingham & Brantingham, 1995). Each of these four theories/perspectives provides a unique contribution to the understanding of the criminal event. Their shared assumptions make them complementary, rather than competing, explanations of crime. In addition, a policing approach called problem-oriented policing draws heavily from routine activities theory to help understand and interrupt the opportunity structures that produce specific crime problems.

The theories and perspectives reviewed here all point to opportunity blocking for prevention. Environmental criminology and other criminological theories make different predictions about how offenders will respond to blocked opportunities. Displacement and diffusion of benefits, described later, are two possible offender adaptations to blocked criminal opportunities for crime.

A. The Rational Choice Perspective

Whereas routine activities theory describes the necessary elements of a criminal event and the controllers who can disrupt that event, the rational choice perspective addresses the processes by which offenders make decisions. Clarke and Cornish (1985) argued that the decision to offend actually comprises two important decision points: (1) an involvement decision and (2) an event decision. The involvement decision refers to an individual’s recognition of his or her readiness to commit a crime (Clarke & Cornish, 1985). The offender has contemplated this form of crime and other potential options for meeting his or her needs and concluded that he or she would commit this type of crime under certain circumstances. This involvement decision process, according to Clarke and Cornish, is influenced by the individual’s prior learning and experiences. The second decision point— the event decision—is highly influenced by situational factors. Situations, however, are not perceived the same way by all people; instead, the person views them through the lens of previous experience and assesses them using his or her information-processing abilities (Clarke & Cornish, 1985). At times, the information used to make decisions is inaccurate, with judgment being clouded by situational changes, drugs, and/or alcohol. Although this model describes involvement and event decisions as two discrete choices, in reality the two may happen almost simultaneously.

Over time, the involvement decision continues to be shaped by experience. Positive reinforcement from criminal events can lead to increased frequency of offending. The individual’s personal circumstances might change to further reflect his or readiness to commit crime. For example, Clarke and Cornish (1985) pointed to increased professionalism in offending, changes in lifestyle, and changes in network of peers and associates as personal conditions that change over time to solidify one’s continual involvement decision. Conversely, an offender may choose to desist in response to reevaluating alternatives to crime. This decision could be influenced by an aversive experience during a criminal event, a change to one’s personal circumstances, or changes in the larger opportunity context (Clarke & Cornish, 1985). Both the involvement and event decisions can be viewed as rational in that they are shaped by the effort, risks, rewards, and excuses associated with the behavior.

B. Situational Crime Prevention

Situational crime prevention is grounded in the rational choice perspective in that it manipulates one or more elements to change the opportunities for crime and in turn change the decision making of potential offenders. In terms of routine activities theory, situational crime prevention can be viewed as the mechanisms by which controllers (i.e., guardians, place managers, and handlers) discourage crime. Over the past few decades, researchers and criminal justice practitioners alike have used the techniques of situational crime prevention to understand crime problems, develop interventions, and evaluate the effectiveness of those interventions. Situational crime prevention was designed to address highly specific forms of crime by systematically manipulating or managing the immediate environment in as permanent a way as possible, with the purpose of reducing opportunities for crime as perceived by a wide range of offenders (Clarke, 1997). Situational crime prevention techniques focus on effectively altering opportunity structures of a particular crime by increasing the efforts, increasing the risks, reducing the rewards, reducing provocations, and removing excuses (Cornish & Clarke, 2003). On its face, situational crime prevention techniques change the event decision by altering the offender’s perceptions of a specific criminal opportunity. However, it should be noted that an offender’s experience during a criminal event directly affects his or her continual involvement decision over time. Blocked opportunities not only prevent an impending criminal event but might also nudge the offender in the direction of abandoning crime.

C. Crime Pattern Theory

Crime pattern theory provides a framework of environmental characteristics, offender perceptions, and offender movements to explain the spatially patterned nature of crime. It is compatible with routine activities theory because it describes the process by which offenders search for or come across suitable targets. P. J. Brantingham and Brantingham (1981) began with the premise that there are individuals who are motivated to commit crime. As these individuals engage in their target selection process, the environment emits cues that indicate the cultural, legal, economic, political, temporal, and spatial characteristics/features of the area. These elements of the environmental backcloth are then perceived by the offender, and he or she interprets the area as being either favorable or unfavorable for crime. Over time, offenders will form templates of these cues on which they will rely to interpret the environment during target selection.

P. J. Brantingham and Brantingham (1993) argued that one common way offenders encounter their targets is through overlapping or shared activity spaces; in other words, offenders come across their targets during the course of their own routine activities, and therefore the locations of these activities, as well as the routes traveled to these locations, will determine the patterning of crime across space. Brantingham and Brantingham referred to the offender’s home, work, school, and places of recreation as nodes. The routes traveled between these nodes are referred to as the paths of the offender. Finally, edges are those physical and mental barriers along the locations of where people live, work, or play. The offender is most likely to search for and/or encounter targets at the nodes, along paths, and at the edges, with the exception of a buffer zone around each node that the offender avoids out of fear of being recognized. Brantingham and Brantingham argued that crime events will thus be clustered along major nodes and paths of activity, as well as constrained by edges of landscapes. The spatial patterns of crime will reflect these two features: the environmental backcloth and the heavily patterned activity paths, nodes, and edges. In addition, Brantingham and Brantingham noted that some places have particularly high levels of crime because of the characteristics of the activity and people associated with it. Specifically, they suggested that some places are crime generators, in that people travel to these locations for reasons other than crime, but the routine activities at these places provide criminal opportunities. Conversely, other places are crime attractors in that their characteristics draw offenders there for the purpose of committing crimes.

D. Problem-Oriented Policing and Problem Analysis

Police agencies use routine activities theory as part of problem-oriented policing. In addition, researchers, city planners, nonprofit organizations, and private citizens follow the same problem analysis process used in problem-oriented policing to understand and prevent crime problems. Problem-oriented policing (Goldstein, 1979) is a proactive policing approach that focuses on systematically addressing problems that produce numerous crime incidents and calls for service to the police, instead of reacting to and treating each call for service in isolation. The problem, rather than the individual crime incident, becomes the unit of work for the police. Problems are a form of crime pattern. Within problem-oriented policing, police work to define, understand, and prevent problems that generate numerous crime incidents and citizen calls to the police.

Problem-oriented policing is implemented through the use of the SARA process—Scanning, Analysis, Response, and Assessment. The police scan crime data and calls for service to identify crime patterns that are produced by a problem. A problem should be narrowly defined; that is, instead of broadly identifying a “theft problem,” it is important to be specific and identify the problem as “theft of shoes from unsecured lockers at the roller rink during after-school hours.” The police then analyze the problem to understand its characteristics and causes. The crime triangle depicted in Figure 1 is often used to organize the analysis; police collect information on all sides of the triangle, not just on offenders. On the basis of this analysis, the police develop responses to prevent future crimes. These responses go beyond traditional police tools of arrest and citation to include less traditional tools that may help disrupt the causes of the problem. These less traditional approaches involve one or more of the three types of controllers discussed earlier. Finally, police assess the overall impact of the response and alter the process accordingly, depending on the results.

It is during the SARA process that routine activities theory can be applied for prevention. Problem-oriented policing complements research that indicates that crime is not randomly distributed (e.g., Eck, Clarke, & Guerette, 2007); instead, some people are repeatedly victimized, some places are repeatedly the sites of crime, and some people repeatedly offend. Eck (2001) suggested that not only does routine activities theory describe the six elements of a crime event but also that specific types of repeat crime and disorder problems can be connected to these elements. Using the terms wolf, duck, and den, problems of repeat victimization, repeat places, and repeat offending can be seen as a function of both the routine activities of potential offenders, victims, and/or places as well as the absence or ineffectiveness of potential handlers, guardians, and/or managers. This in turn sheds light on what steps should be taken to prevent future crimes stemming from the same problem. A “wolf ” problem reflects the repeated actions of an offender or group of offenders, with absent or ineffective handlers. A “duck” problem is one in which the same individual or group is repeatedly victimized; this repeat victimization can be attributed to both the routine activities and characteristics of the victims as well as the absence of capable guardians. A “den” problem is one in which a place is both attractive to targets and offenders while also having weak or absent place managers. The repeat-place problem in which an apartment building is consistently the site of police calls for service might indicate that place managers, such as the landlord or building manager, need to be encouraged or coerced to take control of the problem. In other words, using routine activities theory during problem analysis reveals the absent or ineffective controller who needs to be empowered or held responsible. Furthermore, it might also reveal the activity patterns that systematically produce the opportunity for the crime and suggest points of intervention.

E. Displacement and Diffusion of Benefits

One common concern when implementing opportunity blocking crime prevention strategies is that crime will simply be displaced. In other words, a particular crime event that appears to be prevented is inevitably displaced to another time, place, and/or victim. Different theories of crime make different predictions about the likelihood of displacement in response to blocked criminal opportunities (Clarke, 1997). Traditional criminological theories of offenders suggest that displacement is inevitable when an opportunity for crime is blocked. This prediction is consistent with the assumptions that (a) only offenders matter because (b) crime opportunities are infinite and evenly spread across time, space, and people. These theories suggest that motivated offenders will adapt and simply move on to another available opportunity. Conversely, opportunity theories such as routine activities theory suggest that displacement is possible, but only to the extent that other available criminal opportunities have similar rewards without an increase in costs to the offender (Clarke, 1997). This prediction is consistent with routine activities theory’s focus on opportunity. Opportunities are not assumed to be infinite and equally gratifying to the offender. The likelihood of displacement, therefore, is tied to the relative costs and benefits of alternative crime opportunities. If an offender is unaware of alternative crime opportunities or these alternatives are very unattractive (i.e., they are difficult, risky, or less rewarding), then displacement is unlikely.

There is another possible offender adaptation to crime prevention strategies. Not only might displacement not occur, but also it is possible that the gains from a strategy might extend beyond those crimes that were directly targeted by the strategy. One explanation for this diffusion of benefits is that offenders, uncertain of the actual scope of a particular strategy, refrain from offending in situations beyond the scope of the strategy (Clarke & Weisburd, 1994). Opportunity theories, such as routine activities theory, predict that there may be a diffusion of benefits in response to opportunity blocking if other crimes share similar opportunity structures with those crimes targeted by the strategy. Conversely, dispositional theories of crime generally cannot account for diffusion of benefits.

Environmental criminologists have dedicated considerable attention to the issue of displacement, producing a body of research on displacement that suggests that displacement is not inevitable, nor is it complete when it does occur. Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest that there is sometimes a diffusion of benefits in response to crime prevention strategies. Hesseling (1994) reviewed 55 published articles and reports suggesting that displacement does not appear to be inevitable. When it does occur, it tends to be limited. Of the 55 studies Hesseling reviewed, 22 found no sign of displacement. Six of these studies reported some diffusion of benefits to crimes beyond those directly targeted. Of the 33 studies that reported displacement, no study found complete displacement. The displacement that did occur generally reflected a shift in time, place, target, or tactic for the offender.

V. Future Directions

Although routine activities theory has informed a wealth of research to date, there are still many avenues of research yet to be exhausted. Several areas of research informed by routine activities theory are in their early stages. Guardianship is one of the earliest concepts within routine activities theory, yet there is relatively little understanding of the various forms of guardianship, when and where these forms are effective, and the means by which guardianship reduces crime. On a superficial level, guardianship appears to deter offending by increasing the likelihood the offender will be detected and sanctioned. As many guardians have limited authority, skills, or means to detect and sanction offenders, one may wonder whether (a) guardianship can be based on some other mechanism other than deterrence or (b) many of the examples of guardianship we assume are effective are really guarding; perhaps other things are preventing crime. More research needs to examine this topic.

Another area for research is the concepts of place manager and management. Recently, the Madensen ORCA model of management unpacks these concepts. It states that place management consists of four activities: (1) the Organization of physical space, (2) the Regulation of conduct, (3) the Control of access, and (4) the Acquisition of resources. The study of management and its influence on crime will have to address all four activities and merge crime science with business and management science.

Handlers have received very little attention by routine activity researchers, relative to guardians and managers, yet recent evidence suggests that they may have powerful influences on crime and crime patterns. Tillyer (2008) showed how the concept of handling can be used to reduce a wide variety of crime, from minor juvenile delinquency to group-related homicide.

Crime concentrations appear when none of the controllers is present or effective and offenders meet targets, but why is these controllers absent or ineffective? One answer might be that the controllers whom Rana Sampson (1987), a consultant on problem-oriented policing, calls super controllers are not exerting sufficient or the right influence on the controllers. Super controllers are people and institutions that control controllers. For example, a bartender and bar owner are managers, and the state liquor regulatory agency is one of their super controllers. Foster parents are handlers of children put in their care. Child welfare agencies act as their super controllers. A security guard is a guardian, and the company that hired the guard is a super controller. There is almost no research in this area, although it holds great promise for understanding crime and developing prevention.

Routine activities theory focuses on offenders making contact with targets at places. Some crimes, however, involve “crime at a distance.” Mail bombers, for example, do not come close to their targets. Internet fraudsters are able to steal from victims from anywhere in the world. Either routine activities theory is limited to place-based crimes or it needs revision. Eck and Clarke (2003) suggested that substituting system for place solves the problem. Systems connect people, and they are governed by managers. The mail bomber uses the postal system to contact his victim, and the Internet fraudster uses a system of networked computers. Research on routine activities in systems is in its infancy.

Although it is possible to study the contribution of elements of routine activities theory to the study of crime, it is impossible to empirically study all the elements interacting to create crime patterns. That is because even our best sources of information contain data on only one or two of the actors involved: offenders, targets, handlers, guardians, and managers. Also, the best data available are often highly aggregated and rife with errors. Computer simulations of crime patterns, however, provide a method for exploring how these parts interact in a dynamical system. This is a very new area of research that has spawned simulations of a wide variety of crime types: drug dealing, burglary, robbery, welfare fraud, and others (Liu & Eck, 2008).

VI. Conclusion

To summarize, routine activities theory is a theory of crime events, which distinguishes it from a majority of criminological theories that focus on explaining why some people commit crimes. Although routine activities theory was initially used to explain changes in crime trends over time, it has been increasingly used much more broadly to understand and prevent crime problems. Routine activities theory has guided research designed to understand a range of phenomena, including crime trends over time, distributions of crime across space, and individual differences in victimization. It also has been used in conjunction with many crime control strategies, including problem-oriented policing and problem analysis. Despite the broad applicability of the theory to date, there are numerous directions for future research. Examples include further research on the controllers of crime as well as the super controllers.

Note

1. Cohen and Felson (1979) calculated their household activity ratio by summing the number of married, husband-present female labor force participant households and the number of nonhusband– wife households and then dividing by the total number of households in the United States.

References:

- Brantingham, P. J., & Brantingham, P. L. (1981). Notes on the geometry of crime. In P. L. Brantingham & P. J. Brantingham (Eds.), Environmental criminology (pp. 27–54). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- Brantingham, P. J., & Brantingham, P. L. (1993). Nodes, paths, and edges: Consideration on the complexity of crime and the physical environment. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 13, 3–28.

- Brantingham, P. L., & Brantingham, P. J. (1995). Criminality of place: Crime generators and crime attractors. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, 3, 5–26.

- Clarke, R.V. (1997). Introduction. In R.V. Clarke (Ed.), Situational crime prevention: Successful case studies (pp. 3–36). Guilderland, NY: Harrow & Heston.

- Clarke, R. V. (1999). Hot products: Understanding, anticipating and reducing demand for stolen goods (Paper 112, B. Webb Ed.). London: Home Office, Research Development and Statistics Directorate.

- Clarke, R. V., & Cornish, D. B. (1985). Modeling offenders’ decisions: A framework for research and policy. In M. Tonry & N. Morris (Eds.), Crime and justice: A review of research (Vol. 6, pp. 147–185). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Clarke, R. V., & Weisburd, D. (1994). Diffusion of crime control benefits: Observations on the reverse of displacement. In R. V. Clarke (Ed.), Crime prevention studies (Vol. 2, pp. 165–183). Monsey, NY: Criminal Justice Press.

- Cohen, L. E., & Felson, M. (1979). Social change and crime rate trends: A routine activities approach. American Sociological Review, 44, 88–100.

- Cornish, D. B., & Clarke, R. V. (2003). Opportunities, precipitators and criminal decisions: A reply to Wortley’s critique of situation crime prevention. In M. J. Smith & D. B. Cornish (Eds.), Crime prevention studies: Vol. 16. Theory for practice in situational crime prevention (pp. 41–96). Monsey, NY: Criminal Justice Press.

- Eck, J. E. (1994). Drug markets and drug places: A case-control study of the spatial structure of illicit drug dealing. Baltimore: University of Maryland Press.

- Eck, J. E. (2001). Policing and crime event concentration. In R. Meier, L. Kennedy, & V. Sacco (Eds.), The process and structure of crime: Criminal events and crime analysis, theoretical advances in criminology (pp. 249–276). New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction.

- Eck, J. E. (2003). Police problems: The complexity of problem theory, research and evaluation. In J. Knutsson (Ed.), Crime prevention studies: Vol. 15. Problem-oriented policing: From innovation to mainstream (pp. 79–113). Monsey, NY: Criminal Justice Press.

- Eck, J. E., & Clarke, R. V. (2003). Classifying common police problems: A routine activity approach. In M. J. Smith & D. B. Cornish (Eds.), Crime prevention studies: Vol. 16. Theory for practice in situational crime prevention (pp. 7–39). Monsey, NY: Criminal Justice Press.

- Eck, J. E., Clarke, R.V., & Guerette, R. T. (2007). Risky facilities: Crime concentration in homogeneous sets of establishments and facilities. In G. Farrell, K. Bowers, K. D. Johnson, & M. Townsley (Eds.), Crime prevention studies: Vol. 21. Imagination for crime prevention (pp. 225–264). Monsey, NY: Criminal Justice Press.

- Felson, M. (1986). Routine activities, social controls, rational decisions, and criminal outcomes. In D. Cornish & R. V. Clarke (Eds.), The reasoning criminal (pp. 119–128). New York: Springer-Verlag.

- Felson, M. (1995). Those who discourage crime. In J. E. Eck & D. Weisburd (Eds.), Crime prevention studies: Vol. 4. Crime and place (pp. 53–66). Monsey, NY: Criminal Justice Press.

- Felson, M., & Cohen, L. E. (1980). Human ecology and crime: A routine activity approach. Human Ecology, 8, 389–405.

- Fisher, B. S., Cullen, F. T., & Turner, M. G. (2002). Being pursued: A national-level study of stalking among college women. Criminology and Public Policy, 1, 257–308.

- Goldstein, H. (1979). Improving policing: A problem-oriented approach. Crime & Delinquency, 25, 236–258.

- Hesseling, R. B. P. (1994). Displacement: A review of the empirical literature. In R. Clarke (Ed.), Crime prevention studies (Vol. 3, pp. 197–230). Monsey, NY: Criminal Justice Press.

- Liu, L., & Eck, J. E. (2008). Artificial crime analysis systems: Using computer simulations and geographic information systems. Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

- Messner, S. F., & Blau, J. R. (1987). Routine leisure activities and rates of crime: A macro-level analysis. Social Forces, 65, 1035–1052.

- Miethe, T. D., Stafford, M. C., & Long, J. S. (1987). Social differentiation in criminal victimization:A test of routine activities/ lifestyle theories. American Sociological Review, 52, 184–194.

- Mustaine, E. E., & Tewksbury, R. (1998). Predicting risks of larceny theft victimization: A routine activity analysis using refined lifestyles measures. Criminology, 36, 829–858.

- Sampson, R. J. (1987). Personal violence by stranger: An extension and test of the opportunity model. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 78, 327–356.

- Sampson, R. J., & Wooldredge, J. (1987). Linking the micro- and macro-level dimensions of lifestyle-routine activity and opportunity models of predatory victimizations. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 3, 371–393.

- Tillyer, M. S. (2008). Getting a handle on street violence: Using environmental criminology to understand and prevent repeat offender problems. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Cincinnati.

- Wilcox, P., Land, K. C., & Hunt, S. A. (2003). Criminal circumstance: A dynamic, multi-contextual criminal opportunity theory. New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

- Wilcox Rountree, P., Land, K. C., & Miethe, T. D. (1994). Macro–micro integration in the study of victimization: A hierarchical logistic model analysis across Seattle neighborhoods. Criminology, 32, 387–414.