The prediction of sexual recidivism is one of the most difficult tasks in forensic psychology since human behavior is dependent upon a variety of different factors. Yet assessing risk of recidivism in sexual offenders is an important societal and legal issue because it guides decisions concerning public safety and adequate treatment planning for sexual offenders. Two actuarial risk assessment instruments (ARAIs), the Stable-2007 and the Acute-2007, encompass risk factors that are able to change slowly (i.e., stable) or quickly (i.e., acute) and are therefore amenable for offender treatment programs to reduce the risk to sexually reoffend. By assessing dynamic risk factors, the Stable-2007 and Acute-2007 predict the probability to reoffend in adult male sexual offenders. This article provides a snapshot of recidivism risk prediction and static and dynamic risk factors, then focuses on the Stable-2007 and the Acute-2007, their development as well as their items, scoring, and validity. Actuarial Prediction of Recidivism Risk In order to predict the recidivism risk of sexual offenders, clinicians started to assess offenders based on their subjective experiences after some personal contact with the person concerned. However, Paul E. Meehl demonstrated in 1954 that intuitive judgments, even if they were conducted by experienced clinicians, performed not better than by chance. Meehl revealed that explicitly defined risk factors (e.g., the number of previously committed crimes) that were empirically linked to an increased recidivism risk were more accurate than intuitively established clinical risk factors. He defined the former as the actuarial method of prediction, which has at least two main characteristics: First, there is an explicit rule of combining risk factors (e.g., summing up all scores to one total score), and second, this sum is linked to an empirically derived probability figure (e.g., the probability to reoffend). Structured prediction methods, especially actuarial methods, are state-of-the-art tools in the prediction of recidivism risk in sexual offenders. Static and Dynamic Risk Factors Every ARAI consists of a number of risk factors that have to be combined in an explicit manner. These risk factors have different characteristics related to their stability over time. Risk factors are categorized as static or dynamic depending on whether or not they are potentially prone to change. Static risk factors are characteristics of an offender, which are unchangeable, such as the criminal history (e.g., the number of prior offenses) or victim characteristics. Static risk factors provide information about the status risk of an offender compared to the population he belongs to. Due to their clear operationalization, static risk factors can be easily rated based on file information, which leads usually to a high interrater reliability of these ARAIs. Dynamic risk factors are amenable to change and can be further divided into stable or acute dynamic risk factors depending on the rapidity of change. Stable dynamic risk factors last usually longer time periods (e.g., months or years), but they could be potentially modified, for example, by treatment. Examples of stable risk factors are risk-related traits (e.g., lack of concern for others or impulsivity), sexual self-regulation deficits […]

Criminal Justice Research Papers

Spousal Assault Risk Assessment (SARA)

The Spousal Assault Risk Assessment (SARA) is a structured clinical judgment screening tool used by clinicians, mental health providers, and other professionals to evaluate the risk of future violence in persons who are accused or convicted of spousal assault or intimate partner violence (IPV). The SARA was developed by the British Columbia Institute Against Family Violence, the British Columbia Forensic Psychiatric Services Commission, and several other agencies as part of the Project for Protection of Victims of Spousal Assault. After a brief discussion of IPV in today’s society, this article focuses on the uses, completion process, and reliability and validity of the SARA. IPV IPV is prevalent in today’s society. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 2014 Understanding Intimate Partner Violence Fact Sheet, every minute, 24 people are victims of IPV, including more than 12 million men and women each year. IPV is associated with psychological distress, poor cognitive functioning, depression, drug and alcohol abuse, and suicide. The 2010 National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey reported that approximately one in four women and one in 10 men who have experienced IPV report short-term and long-term symptoms of post-traumatic stress and other emotional difficulties. For these reasons, risk assessment tools, such as the SARA, are in high demand to aid in the management and treatment of the offender and to reduce the likelihood of recidivism. Completing the SARA Accurate completion of the SARA requires collecting a large amount of data on the client, including interviewing the defendant/offender, and victim; completing standardized measures of physical and emotional abuse as well as standardized measures of alcohol and drug abuse, reviewing collateral information (e.g., police reports, criminal offense records); and using other psychological assessment procedures (i.e., personality inventories, cognitive testing and clinical interviews with children, relatives, and/or probation officers). Suggested standardized measures are included in the user’s manual. After completing these procedures and measures, the clinician rates the client on 20 items on a 3-point scale (0 = absent, 1= possible or partially present, 2 = present), which are grouped into four risk areas: criminal history (i.e., history of assault), psychosocial adjustment (i.e., mental disorders, recent stressors), spousal assault history, and elements of alleged/most recent offense (i.e., use of weapon). The overall risk designation is determined by the clinician and not necessarily tied to the sum of the items. Also contained within the SARA is a section titled Other Considerations that allows for the clinician or mental health professional to note important risk factors not incorporated within the SARA. The user’s manual includes the scoring instructions. Uses of the SARA The SARA has been used throughout various stages of the criminal justice process. The SARA can be used during the pretrial phase to assist the judge in determining whether the accused should be granted pretrial release. If the accused is seen as a threat to his or her spouse and/or others, the individual may not be granted bail. The SARA can also be used during the presentencing phase when […]

Short-Term Assessment of Risk and Treatability: Adolescent Version (START: AV)

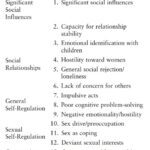

The START:AV is a structured risk assessment tool designed to assess and manage short-term (i.e., 3 months) risk of multiple adverse outcomes among male and female adolescents in mental health and/or criminal justice settings. Adverse outcomes included within the START:AV are categorized into two broad domains: Harm to Others and Rule Violations (i.e., violence, nonviolent offenses, substance abuse, and unauthorized absences) and Harm to the Adolescent (i.e., suicide, non-suicidal self-injury, victimization, and health neglect). The START:AV adheres to the structured professional judgment model of risk assessment and is an adapted version of the Short-Term Assessment of Risk and Treatability designed for use with adult psychiatric populations. The START:AV is relevant to correctional psychology, as it not only helps to guide the assessment and management of risk of violent and nonviolent offending but also provides a comprehensive assessment of other adverse outcomes that are considered critical to an adolescent offender’s well-being. The current entry describes the START:AV and discusses its purpose and development and provides a brief overview of the empirical findings regarding its reliability and validity. Description and Purpose of the START:AV The START:AV comprises 25 items, 24 of which fall into three clusters: Individual Adolescent, Relationships and Environment, and Response to Interventions (see Table 1 for a list of the items by cluster). Embedded within the START:AV is an additional case-specific item (i.e., Item 25) that allows for the assessor to incorporate any information pertinent to the assessment that is not otherwise captured by the other 24 items (e.g., culture). All items of the START:AV are considered modifiable (i.e., dynamic in nature), and unlike other contemporary risk assessment tools such as the Structured Assessment of Violence Risk in Youth, the START:AV does not separate items based on whether they are risk or protective factors; rather, each item is simultaneously rated as both a Strength (i.e., a feature or characteristic that decreases risk of an adverse outcome) and a Vulnerability (i.e., a feature or characteristic that increases risk of an adverse outcome). For example, an adolescent can display both strengths and vulnerabilities within a single area such as a youth who primarily associates with antisocial peers, yet maintains contact with some prosocial peers (e.g., Item 17: Peers). As such, ratings of Strengths and Vulnerabilities may or may not correspond with each other. Each item is rated as low, moderate, or high based on whether an adolescent has displayed minimal, some, or substantial Strengths or Vulnerabilities within a specific area over the past 3 months. In rating the items, assessors are to use adolescents who are of a similar age in the general population as a reference for comparison. After each individual item is rated, Key Strengths (i.e., items that are considered to be instrumental in decreasing or buffering a youth’s risk) and Critical Vulnerabilities (i.e., items that are considered to be instrumental in increasing or driving a youth’s risk) are identified. However, not every Strength or Vulnerability rated as high need be identified as a Key Strength or Critical Vulnerability, […]

Short-Term Assessment of Risk and Treatability (START)

The Short-Term Assessment of Risk and Treatability (START) is a succinct structured professional judgment guide for the assessment of dynamic vulnerabilities and strengths associated with risk of violence, self-harm, suicide, unauthorized leave, substance abuse, self-neglect, and being victimized by others. Working with individuals in criminal justice, psychiatric, and community mental health contexts calls for practitioners to identify the risks that individuals might pose to themselves or others (e.g., violence, suicide, non-suicidal self-injury) and to effect management plans to prevent undesirable outcomes (e.g., mental illness relapse, rehospitalization, violence, recidivism, substance use relapse, suicide, self-harm). Given the pervasive risks to self and others in these populations and the substantial personal and social burdens, risk assessment is a process with inherently high stakes. It is fraught with challenges, including the potential for liability risk and ethical issues for the assessor, reduced civil liberties for the individual, stigma for the population, and economic implications and safety concerns for the public. Considerable investment has been made in exacting how best to conduct risk assessments and to translate those findings into effective risk management plans. The START is one such endeavor. The START has been recognized by several agencies (e.g., Accreditation Canada, UK Department of Health) and experts as a promising, leading, or best practice in the assessment and management of violence and related risks. It is being used across the globe in correctional, forensic, and mental health institutions and community programs. As of 2018, there were nine language translations (Danish, Dutch, Finnish, French, German, Norwegian, Spanish, Swedish, and Thai; with Italian, Japanese, and Russian translations in preparation) and more than 50 published articles on the START. There also is a version for use with youth aged 13–18 years, the START: Adolescent Version. This article begins by discussing the development, key characteristics, and use of the START; then the entry focuses on the research evidence for the START. Development and Key Characteristics The START was developed in the early 2000s in direct response to limitations of existing risk assessment measures, as identified in the research literature and by direct care providers and clinicians. The START is unique compared to other risk assessment measures because of several key characteristics, including its focus on dynamic factors, strengths and vulnerabilities, and multiple short-term adverse outcomes. Dynamic Factors START assessments focus on an individual’s current functioning on dynamic factors, within the context of their history. Historical, static factors (i.e., unchangeable variables, such as a history of child abuse, criminal record) and stable factors (i.e., variables that can change but that often are difficult or slow to change, such as antisocial attitudes) provide essential insights into future behavior and effective risk management endeavors. However, research also demonstrates the value of dynamic factors (i.e., changeable variables, such as social support), particularly in imminent, acute, and short-term assessments. Moreover, good clinical and criminal justice practice demands that assessors are attentive not only to factors that increase risk but also those that can be changed through intervention. Strengths and Vulnerabilities The START acknowledges that […]

Sexual Violence Risk-20 (SVR-20)

Risk assessment of sexual offenders is an important topic in forensic psychiatry and psychology. Practitioners are given the responsibility of completing risk assessments of offenders to try to maximize public safety and encourage responsible management, both of which depend on effective intervention and supervision. The basis of the development of the Sexual Violence Risk-20 (SVR-20) was to utilize structured professional judgment (SPJ) to inform risk management to, in turn, maximize public safety, the latter being viewed as the ultimate objective of all risk assessment work. This article focuses on the SVR-20 and its revised version, discussing its guidelines. SVR-20 Guidelines The SPJ approach to risk assessment exemplified by the SVR-20 is based on the use of structured clinical guidelines to help the assessor formulate a risk depiction of the individual being assessed. The use of such guidelines assumes that (a) the assessment is being done by a professional who has been trained, (b) the guidelines include the most important risk factors that should be minimally considered by the evaluator, and (c) the evaluator must use discretion as to how information regarding risk factors is to be combined through the SPJ approach to reach final judgments regarding risk. The SVR-20 guidelines for assessing risk of sexual violence have been widely adopted by clinicians around the world because of the flexibility of the method. The instrument allows for the analysis of various aspects of risk including not just likelihood of reoffense, but also nature, imminence, victim specificity, and severity (e.g., lethality). The SVR-20 guidelines also allow assessors to consider a range of factors that are relevant to the risk assessment at hand, including issues related to sexual disorders (paraphilias) that may be reflected in criminal behavior, such as sadism, fetishism, or pedophilia, all of which help to inform the risk management of the individual being assessed. The original SVR-20, published in 1997, comprised 20 risk factors in three domains: Psychosocial Adjustment, Sexual Offenses, and Future Plans. The domain of Psychosocial Adjustment included sexual deviation, victim of child abuse, psychopathy, major mental illness, substance use problems, suicidal/homicidal ideation, relationship problems, employment problems, past nonsexual violent offenses, past nonviolent offenses, and past supervision failures. Sexual Offenses included high-density sex offenses, multiple sex offense types, physical harm to victims in sex offenses, use of weapons or threats of death in sex offenses, escalation in frequency or severity of sex offenses, extreme minimization or denial of sex offenses, and attitudes that support or condone sex offenses. Future Plans included lacks realistic plans and negative attitude toward intervention. The inclusion of each item was supported by the systematic review of the scientific and professional literatures. Since its publication, and despite some criticisms, the SVR-20 has been evaluated by a variety of researchers in a variety of sites internationally and is considered the best validated SPJ for the risk assessment of sexual offenders. There are a large number of studies showing good to excellent levels of interrater reliability. According to several empirical studies and meta-analyses, judgments of risk […]

Sex Offender Treatment Intervention and Progress Scale (SOTIPS)

The Sex Offender Treatment Intervention and Progress Scale (SOTIPS) is a statistically derived dynamic risk assessment instrument for adult males who have been convicted of sexually abusive behavior. Mental health clinicians, correctional caseworkers, and probation and parole officers use the SOTIPS to assess an individual’s sexual reoffense risk, treatment and supervision needs, and treatment progress. The SOTIPS is designed to be scored at the time an individual begins a treatment or supervision program and thereafter as frequently as every 6 months. The SOTIPS surveys 16 potentially changeable domains (i.e., criminogenic needs or dynamic risk factors) that are related to risk of future sexual offending. The SOTIPS may be used alone or in conjunction with a static sexual offender risk assessment instrument, such as the Static-99R or the Vermont Assessment of Sex Offender Risk-2, which is composed of unchangeable risk factors. When used in conjunction with a static risk instrument, SOTIPS scores can be used to adjust baseline recidivism risk predictions. This article explores the items on the SOTIPS and then explains the criteria for its use, the interpretation of scores, and how to implement this risk assessment tool. SOTIPS Items The 16 SOTIPS items are scored on a scale of 0–3, with higher scores indicating greater treatment need and dynamic risk. Most SOTIPS items are scored to reflect an individual’s cognitive and behavioral functioning for the previous 6 months. SOTIPS items can be clustered into five conceptual categories: sexuality and risk responsibility, criminality, treatment and supervision cooperation, self-management, and social stability and supports. Sexuality and Risk Responsibility The sexuality and risk responsibility category contains 5 items related to sexuality and sexual abuser treatment motivation. The Sexual Offense Responsibility item measures the extent to which an individual internalizes responsibility for his sexual offending behavior. Sexual Behavior measures the proportion of the individual’s non-abusive behavior to offense-supportive sexual behaviors during the previous 6 months. Offense-supportive behavior includes engaging in promiscuous sexual behavior, using pornography in violation of supervision or treatment rules, and engaging in illegal sexual behavior. Sexual attitude addresses the cognitions and beliefs that drive sexually abusive behaviors, including viewing sexual urges as uncontrollable or viewing sexual activity with children as not harmful. Sexual interest quantifies the degree to which the individual’s overall sexual interests focus on offense-related themes, including greater sexual interest in children or rape than interest in consensual sexual activity with consenting adults. Sexual risk management evaluates the individual’s understanding of his risk factors for sexual reoffending and the adequacy of his plan and its implementation to manage his risk in the community. Criminal Behavior The second SOTIPS category contains 2 items that are related to antisocial behaviors and attitudes. Criminal and rule-breaking behavior quantifies behaviors associated with breaking criminal laws, not adhering to probation or parole conditions, or failing to abide by correctional facility rules. Criminal and rule-breaking attitude measures the extent of cognitions and beliefs supporting such behaviors (e.g., “It is only wrong if you get caught” and “Rules are made to be broken”). Treatment and […]

Sex Offender Risk Appraisal Guide (SORAG)

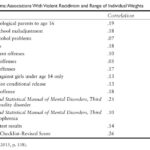

The Sex Offender Risk Appraisal Guide (SORAG) is a 14-item static actuarial risk assessment tool developed to assess risk of general violence (sexual and nonsexual) with adult male sex offenders. After reviewing the development and content of the SORAG, this article discusses its predictive accuracy, strengths, limitations, and applications and concludes with a look at a recent revision merging the SORAG with a companion measure. Development and Item Content The SORAG was developed in 1998 by Vernon Quinsey, Grant Harris, Marnie Rice, and Catherine Cormier at the Mental Health Centre Penetanguishene in Ontario, Canada, a maximum-security psychiatric facility. Although intended to be used with sex offenders, the broad scope of the SORAG is based on the premise that violence as an aggregate outcome is sufficiently serious to merit assessment. For instance, the public is no less deserving of protection from an individual who has committed a nonsexual homicide than an individual who has committed a sexual assault. Furthermore, there is evidence that men who commit sexual offenses (e.g., sexual assault of an adult woman, sexual abuse of a child) have some unique risk factors that set them apart from other violent offenders (e.g., deviant sexual interests, sexual offense history) which are predictive of violence and enough to justify the development of a separate scale. The SORAG was originally developed on 288 adult male sex offenders from four independent samples who were released from Mental Health Centre Penetanguishene and followed up in the community. The rate of violent recidivism observed in the overall sample was 42% over 7 years and 58% over 10 years. The items for the SORAG were identified through statistical procedures aimed at identifying combinations of predictors that optimized the prediction of violence. In all, 14 variables that discriminated violent recidivists from nonrecidivists are listed in Table 1. The correlation for each individual item with binary violent recidivism (i.e., yes–no violently reoffended) is presented in Table 1, along with the weighting of each item. Briefly, correlations are statistics ranging in value from −1.0 to +1.0 representing the strength of association between two variables. When a correlation is computed between one binary variable (i.e., a variable that can take one of only two values, such as inpatient or outpatient or criminally insane or not criminally insane) and another variable with a range of values, this is called a point biserial correlation. Point biserial correlations from .10 to .23 are considered small in magnitude, while those ranging from .24 to .36 are moderate and .37 and above are high. These 14 items were used as the foundation for developing the SORAG. After the best predicting items were identified, a technique known as the Burgess method was used to differentially weight predictor variables shown to successfully discriminate violent recidivists from nonrecidivists. For each category or value of a predictor demonstrating a 5% increase or decrease in recidivism from the overall rate, a weighting of +1 or −1, respectively, is assigned. The weights are increased in either direction based on the degree […]

Self-Report Psychopathy (SRP)

The Self-Report Psychopathy (SRP) scale was designed by Robert D. Hare as a self-report version of his Psychopathy Checklist (PCL) and its revision (PCL-R). Originally created using correctional and forensic populations, the PCL-R is a 20-item construct rating scale that conceptualizes psychopathy as a superordinate dimensional construct composed of four correlated factors: interpersonal (glibness/superficial charm, grandiose sense of self-worth, pathological lying, conning/manipulative), affective (lack of remorse or guilt, shallow affect, callous/lack of empathy, failure to accept responsibility for actions), lifestyle (need for stimulation/proneness to boredom, parasitic lifestyle, lack of realistic long-term goals, impulsivity, irresponsibility), and antisocial (poor behavioral controls, early behavior problems, juvenile delinquency, revocation of conditional release, criminal versatility). Based on a structured interview and file review, PCL-R items are scored on a 0–2 ordinal scale with a recommended diagnostic cutoff score of 30 or above for research and forensic purposes. The PCL-R is considered the international standard for the assessment of psychopathy and helped to significantly advance understanding of the construct by providing a common metric for researchers and clinicians. However, as with any psychiatric interview, the PCL-R requires extensive training and skilled clinicians or researchers to administer it. Thus, the time and cost to train and administer the PCL-R, along with the low prevalence of clinically diagnostic psychopathy in the general population (approximately 1%), lead it to be less practical for non-forensic settings. In addition, certain PCL-R items that are relevant in offender settings (e.g., revocation of conditional release, criminal versatility) may not be appropriate for community samples. For research in the general population, Hare and colleagues developed the SRP. This article focuses on the development and utility of the SRP, as well as its strengths and critique of other psychopathy self-report measures. SRP Development Hare developed the initial versions of both the SRP and the PCL in 1985 after finding that early measures used to assess psychopathy (e.g., Psychopathic Deviate scale from the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory and the Socialization scale from the California Psychological Inventory) had weak associations with each other and the early PCL. The SRP was developed using standard item reduction procedures to identify items related to psychopathy. Despite developing the initial SRP in the same theoretical framework as the PCL, the agreement between the two instruments was modest. To refine the SRP, Hare and colleagues developed the SRP-II in 1991 to reflect the two-factor structure of the PCL-R. Factor 1 of the PCL-R includes the interpersonal and affective components of psychopathy, and Factor 2 combines lifestyle and antisocial factors. To reflect the PCL-R changes, the SRP-II was expanded to a comprehensive 60-item measure with 31 items specifically designed to capture the two-factor structure. The validity of the SRP-II was bolstered by robust positive correlations with the PCL-R in both clinical and forensic samples. In non-forensic settings, Delroy Paulhus and his colleagues found that SRP-II total scores correlated positively with a variety of antisocial behavioral (e.g., delinquency) and personality (e.g., disagreeableness, promiscuous sexual attitudes) variables. Despite these positive findings, Paulhus and his colleagues […]

Self-Report Measures of Psychopathy

The use of self-report measures to assess psychopathic personality or psychopathy (i.e., a constellation of personality traits and behaviors encompassing guiltlessness, superficial charm, grandiosity, callousness, poor impulse control, and manipulativeness) has been fraught with controversy. Until approximately the 1990s, the overwhelming majority of psychopathy research was conducted in forensic and clinical settings. Since the 1990s, however, interest in studying psychopathic traits in nonclinical settings, such as college and community samples, has burgeoned. Moreover, accumulating research evidence suggests that psychopathy differs in degree rather than kind from normality and is probably underpinned by one or more subdimensions. Given these findings, some researchers have argued that psychopathy can be studied profitably among noncriminal populations by means of self-report measures. Self-report measures have become the predominant mode of psychopathy assessment among nonclinical participants, such as those in college and community samples. This article addresses the potential disadvantages and advantages of self-report psychopathy measures. Criticisms and Potential Disadvantages Self-report psychopathy measures have been met with some criticism. Critics of self-report psychopathy measures point to a variety of features associated with psychopathy, including dishonesty, manipulativeness, grandiose sense of self, and lack of insight, which preclude individuals’ ability to report accurately on their attributes. These criticisms typically reflect skepticism that individuals with extreme psychopathic features are either unwilling or unable to present themselves accurately. This notion is held widely in clinical psychology and psychiatry circles, even among psychopathy researchers. Dishonesty The most obvious characteristics of psychopathy believed to adversely affect the validity of self-reports are dishonesty and manipulativeness. Psychiatrist Hervey Cleckley, who introduced the psychopathy construct to the clinical community in 1941, noted astutely that “the psychopath shows a remarkable disregard for truth.” The lion’s share of research investigating this concern has focused on psychopathy’s relations with response bias, reflecting either a conscious or an unconscious motivation to present oneself inaccurately. Nevertheless, when examined meta-analytically, psychopathy does not relate markedly to various indices of response bias, such as social desirability. In fact, psychopathy is typically negatively associated with underreporting of negative features (i.e., faking good) and positively associated with overreporting of negative features (i.e., faking bad). Contrary to clinical lore, psychopathic individuals are willing to admit to many socially undesirable characteristics and are consistent with higher levels of negative emotionality found in those with chronic antisocial behaviors and impulsivity, which are commonly associated with psychopathy. Lack of Insight A second characteristic of psychopathic individuals thought to adversely affect their self-reports is lack of insight. Cleckley conjectured that psychopathic individuals lack the capacity to see themselves as others see them, calling into question their ability to introspect accurately. Nevertheless, scant research has examined blind spots in psychopathic individuals’ self-perception. It is well established that psychopathic individuals are higher in blame externalization, a trait that is assessed explicitly in certain self-report psychopathy measures. Although there are several potential explanations for this finding, the presence of elevated levels of this trait leaves open the possibility that psychopathic individuals possess little insight into their problematic behavior. Self-Report Versus Informant Report […]

Self-Appraisal Questionnaire (SAQ)

The Self-Appraisal Questionnaire (SAQ) is a theoretically and empirically based instrument. It is the first multidimensional self-administered questionnaire that was specifically designed to predict violent and nonviolent offender recidivism among correctional and forensic populations and to assist with the assignment of these populations to appropriate treatment or correctional programs and different institutional security levels. It was designed to be multifaceted, covering content areas that have been demonstrated to be important for measuring criminogenic factors related to the assessment of recidivism and treatment of offenders. After further describing the SAQ, this article discusses its uses, describes how to score and interpret, and reviews its reliability, validity, and advantages. Description of the SAQ The SAQ was developed in 1996 and published in 2005 with the Mental Health Systems, Toronto. It was designed to cover the predominant predictive areas found in the offender recidivism literature, as some of these areas were ignored or not adequately covered by other tools. The SAQ consists of 72 items, with seven subscales that measure quantitative criminogenic risk/need areas. The first subscale, Criminal Tendencies, taps antisocial attitudes, beliefs, behaviors, and feelings. These tendencies are considered central to the major theories of criminality and the prediction of recidivism. Previous studies, including meta-analysis studies, indicated that the best individual predictors of recidivism were attitudes, values, and behaviors that support a criminal lifestyle. The second SAQ subscale is Antisocial Personality Problems. This subscale covers characteristics similar to those used to diagnose antisocial personality disorder, which has been the psychiatric diagnosis traditionally used to predict recidivism. Self-reported antisocial personality characteristics have been shown to predict static and dynamic factors of violent recidivism. The third subscale, Conduct Problems, assesses childhood behavioral problems. Research has indicated that conduct problems during childhood are among the best predictors of later offending and the development of a criminal career. The fourth subscale considers the offender’s Criminal History, as past criminality has been shown to be a robust predictor of future criminal acts. The fifth subscale is Alcohol/Drug Abuse. The relationship between substance abuse and crime, including violence, is well documented and has been found to correlate with recidivism. The sixth subscale assesses Anti-Social Associates, an area with demonstrated value in the prediction of recidivism. The seventh subscale, Anger, measures the offender’s reaction to anger. This scale is not included in the total score of the SAQ due to the controversial and unconfirmed relationship between anger and recidivism. This subscale could be useful in assigning offenders to anger management or control programs. The Validity scale is a subscale that can be used to validate the offender’s truthfulness in responding to the SAQ’s items. Uses of the SAQ The SAQ can be used for several purposes. First, the SAQ can be used to predict post-release adjustment such as violent and nonviolent recidivism, parole violations, and probability of being convicted of a new offence. The SAQ can also be used to assign offenders to institutional security levels and predict institutional adjustment. Another purpose of the SAQ is the assignment of […]