The Psychopathic Personality Inventory-Revised (PPI-R) is the revised version of the Psychopathic Personality Inventory (PPI), a widely used self-report measure of psychopathic personality (psychopathy). The PPI-R, like its predecessor, is designed to detect the core personality traits of psychopathy, including superficial charm, fearlessness, guiltlessness, manipulativeness, dishonesty, grandiosity, callousness, externalization of blame, and poor impulse control. It excludes items explicitly assessing overt antisocial and criminal behaviors to permit investigators and clinicians to focus on psychopathic personality traits per se. As a consequence, compared with many other psychopathy indices, the PPI-R may better distinguish psychopathy from the conceptually and empirically overlapping construct of antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. ASPD, in contrast to the largely personality-based condition of psychopathy, is operationalized in terms of a long-standing antisocial and criminal behavior and is virtually by definition maladaptive.

Prior to the development of the PPI, most research on psychopathy was limited to offenders, largely because most extant measures of this condition required access to detailed corroborative (e.g., file) information. Perhaps partly as a consequence of the field’s focus on criminal samples, most psychopathy measures were largely maladaptive in content. In contrast, the PPI-R helps to detect both the largely adaptive (e.g., superficial charm, social poise, adventure seeking), and largely maladaptive (e.g., poor impulse control, callousness, dishonesty) features of psychopathy. Although initially intended to identify psychopathic individuals in noncriminal settings, such as those in student, community, and business samples, the PPI-R has since been used extensively in a variety of forensic contexts. This article reviews the construction and structure of the PPI-R and then discusses its reliability and validity.

Construction of the PPI and PPI-R

The PPI consisted of 187 self-report items arrayed in 1–4 Likert-type format (1 = false, 2 = mostly false, 3 = mostly true, and 4 = true). It was developed over the span of several years in the late 1980s. The initial focal constructs considered for inclusion in the PPI were derived from a comprehensive review of the clinical and research literatures on psychopathy, including the seminal writings of Hervey Cleckley, Benjamin Karpman, David Lykken, Robert Hare, Joan and William McCord, Marvin Zuckerman, and Herbert Quay.

PPI items were written to be accessible and understandable by a broad range of respondents. To enhance the likelihood that psychopathic respondents would be willing to endorse trait- relevant items, most PPI items were phrased to be socially normative. For example, a PPI item written to assess dishonesty (retained in the PPI-R) is “I tell a lot of ‘white lies,’” which assesses a dishonest action that is both mild and common in the general population. A PPI-R item written to assess grandiosity is “People are impressed with me after they first meet me,” which ostensibly assesses a feature of narcissism that is positively valued. In the initial version of the PPI, approximately an equivalent number of items were keyed in the true and false directions to minimize acquiescence (“yea-saying”) and counter-acquiescence (“naysaying”) response biases.

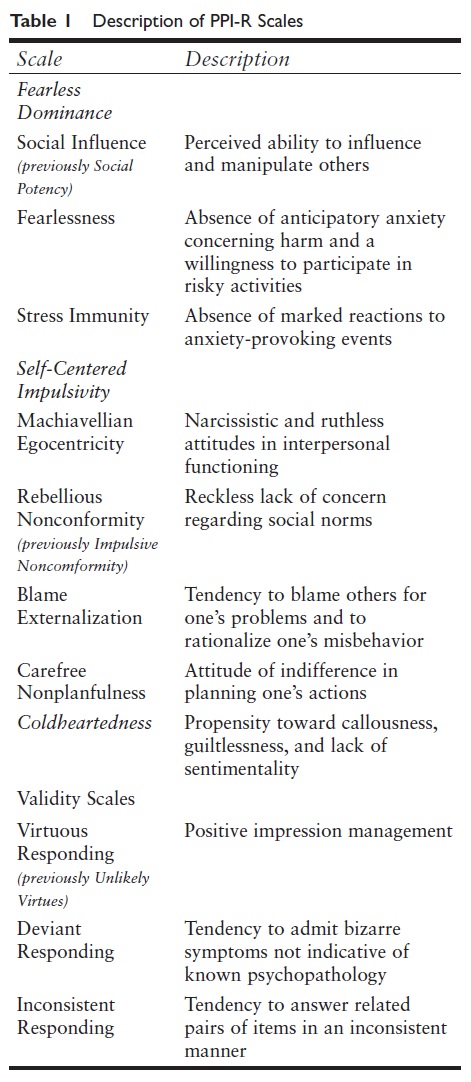

The PPI and PPI-R contain three validity scales designed to detect response biases that may be especially problematic among psychopathic individuals: Deviant Responding, Virtuous Responding, and Inconsistent Responding. Deviant Responding, intended to detect malingering and otherwise aberrant responding, consists of questions that assess largely or entirely nonexistent signs and symptoms of psychopathology (e.g., “I look down at the ground whenever I hear an airplane flying above my head”). Virtuous Responding (called Unlikely Virtues in the PPI), intended to assess positive impression management, consists of questions that assess denial of common frailties (e.g., “Every once in a while, I nod my head when people speak to me even though I’m not paying attention to them,” keyed in the false direction). Inconsistent Responding (called Variable Response Inconsistency in the PPI), intended to detect random or careless responding, consists of item pairs in which the items are moderately to highly correlated; numerous inconsistent responses to the items within each pair generate a high score. For example, 2 PPI-R items ask about fears of parachute jumping in slightly different ways, and respondents who provide markedly different answers to these items gain a point on the Inconsistent Responding Scale.

The PPI items and constructs were progressively refined by means of factor analyses on three successive undergraduate samples, with a total sample size of 1,156 participants. The eight lower order factors comprising the PPI emerged across three rounds of test development and provide a broad, although by no means comprehensive, portrait of the key affective and interpersonal features of psychopathy. These eight subscales are now termed Social Influence ( formerly Social Potency), Fearlessness, Stress Immunity, Machiavellian Egocentricity, Blame Externalization (formerly Alienation), Rebellious Nonconformity (formerly Impulsive Nonconformity), Carefree Nonplanfulness, and Coldheartedness (see Table 1 for descriptions of each subscale).

The PPI was revised (to the PPI-R) in 2005 to reduce its length, decrease its reading level to make it more applicable to forensic (e.g., prison) samples, and eliminate items that were psychometrically suboptimal or that contained culturally specific idioms. Based on factor analyses of large student/community and offender samples, a number of inadequately functioning PPI items were eliminated or revised. In addition, the PPI-R manual provided age- and gender-specific norms for general population (student and community) and offender samples. The PPI-R consists of 154 items divided into the same subscales and three validity scales as the PPI.

Higher Order Factor Structure of the PPI-R

Factor analyses of the PPI-R subscales have often yielded a coherent three-factor structure. Nevertheless, because the PPI and PPI-R were not developed to yield a clear higher order factor structure, this structure does not emerge unambiguously in all samples. In contrast to the factors of most psychopathy measures, those of the PPI-R are largely orthogonal (uncorrelated).

One higher order dimension, termed Fearless Dominance, consists of scores on the Social Influence, Fearlessness, and Stress Immunity subscales. This dimension appears to assess a broad trait that Florida State University psychologist Christopher Patrick and his colleagues term boldness that encompasses social and physical risk-taking, interpersonal poise, emotional resilience, and calmness in the face of stressors. More generally, Fearless Dominance may assess the largely adaptive features of psychopathy that sometimes predispose individuals to success in business, politics, high-risk sports, and other life domains.

A second higher order dimension, termed Self-Centered Impulsivity, consists of scores on the Machiavellian Egocentricity, Blame Externalization, Rebellious Nonconformity, and Carefree Nonplanfulness. This dimension appears to assess a broad trait that Patrick and his collaborators term disinhibition that encompasses poor impulse control, recklessness, narcissistic ruthlessness, and perception of oneself as a victim. In contrast to Fearless Dominance, Self-Centered Impulsivity appears to assess the largely maladaptive features of psychopathy, placing certain individuals at risk of externalizing psychopathology, including criminal behavior and substance abuse. Not surprisingly, this dimension—in contrast to Fearless Dominance—tends to be highly correlated with measures of ASPD.

The PPI-R Coldheartedness does not load highly on either the Fearless Dominance or Self-Centered Impulsivity dimensions and is increasingly treated as a stand-alone dimension in analyses. This dimension appears to assess a trait similar to what Patrick and colleagues term meanness, although Coldheartedness tends to reflect passive emotional detachment rather than active antagonism. More than the other two PPI-R higher order dimensions, Coldheartedness tends to relate (negatively) to measures of affective empathy and guilt.

Reliability

The test–retest reliability of the PPI-R total score (across an average 20-day interval) in a general population sample is .93, which is very high; the test–retest reliabilities of the subscales are similarly high, ranging from .82 to .95. The internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) of the PPI-R total score in the general population is also high (.92), and the internal consistencies of its subscales range from .78 to .87. Nevertheless, the high Cronbach’s alpha for the total score conceals the fact that the average inter-item correlations for the PPI-R total score tend to be low (below r = .10), consistent with the substantial heterogeneity of PPI-R-assessed psychopathy.

Validity

A large body of literature across numerous samples, including college, community, and forensic samples, offers support for the construct validity of the PPI-R. For example, PPI-R total scores correlate moderately to highly with self-report, observer-based (e.g., peer ratings of psychopathy), and interview-based indices of psychopathy, as well as with indices of conditions that overlap with psychopathy, such as narcissistic and histrionic personality disorders. PPI-R total scores are also positively associated with measures of ASPD, although this association is sufficiently modest in magnitude to indicate that the PPI-R distinguishes psychopathy from ASPD. Like most other psychopathy measures, PPI-R total scores relate in theoretically meaningful ways with several traits of the well-accepted five-factor model of personality, especially Agreeableness and Conscientiousness (both negatively). In addition, PPI-R total scores are positively correlated with a broad spectrum of personality traits theoretically tied to psychopathy, such as sensation seeking, interpersonal dominance, grandiose narcissism, impulsivity, and Machiavellianism. Just as important, PPI-R total scores display discriminant validity from measures of constructs that are theoretically separable from psychopathy, such as indices of schizophrenia spectrum disorders, depression, and social desirability.

The PPI-R higher order dimensions display encouraging validity as well. For example, Fearless Dominance tends to be modestly and negatively associated with laboratory measures of fear processing, such as fear-potentiated startle and amygdala activation in response to fear-provoking stimuli, and Self-Centered Impulsivity tends to be positively associated with ventral striatum activation in response to reward-related cues. In addition, Fearless Dominance differentiates psychopathy from ASPD, consistent with the view that the former condition tends to be associated with somewhat more psychologically adaptive traits than the latter.

Nevertheless, the role of Fearless Dominance within the psychopathy construct is controversial. Some authors contend that Fearless Dominance is largely or entirely irrelevant to psychopathy given that it is seemingly adaptive in content and only weakly associated with measures of antisocial and criminal behavior. Along these lines, some authors have questioned or rejected the possibility that certain psychopathic traits can predispose to adaptive outcomes in certain contexts, such as the business or political worlds. In contrast, other authors, ourselves included, regard Fearless Dominance as a key feature of psychopathy given that it accounts largely for the superficial charm, poise, and venturesomeness captured in classic clinical descriptions of the condition, such as those of Cleckley. Interestingly, Fearless Dominance correlates moderately to highly with scores on some psychopathy measures but not others, suggesting that different psychopathy measures differ sharply in their conceptualization and operationalization of this condition. Specifically, some psychopathy measures may be slanted largely toward successful variants of psychopathy, whereas others may be slanted largely toward unsuccessful variants, such as those linked to ASPD.

References:

- Cleckley, H. (1941). The mask of sanity: An attempt to reinterpret the so-called psychopathic personality. St. Louis, MO: Mosby.

- Lilienfeld, S. O., & Andrews, B. P. (1996). Development and preliminary validation of a self-report measure of psychopathic personality traits in noncriminal population. Journal of Personality Assessment, 66, 488–524.