The Sex Offender Risk Appraisal Guide (SORAG) is a 14-item static actuarial risk assessment tool developed to assess risk of general violence (sexual and nonsexual) with adult male sex offenders. After reviewing the development and content of the SORAG, this article discusses its predictive accuracy, strengths, limitations, and applications and concludes with a look at a recent revision merging the SORAG with a companion measure.

Development and Item Content

The SORAG was developed in 1998 by Vernon Quinsey, Grant Harris, Marnie Rice, and Catherine Cormier at the Mental Health Centre Penetanguishene in Ontario, Canada, a maximum-security psychiatric facility. Although intended to be used with sex offenders, the broad scope of the SORAG is based on the premise that violence as an aggregate outcome is sufficiently serious to merit assessment. For instance, the public is no less deserving of protection from an individual who has committed a nonsexual homicide than an individual who has committed a sexual assault. Furthermore, there is evidence that men who commit sexual offenses (e.g., sexual assault of an adult woman, sexual abuse of a child) have some unique risk factors that set them apart from other violent offenders (e.g., deviant sexual interests, sexual offense history) which are predictive of violence and enough to justify the development of a separate scale.

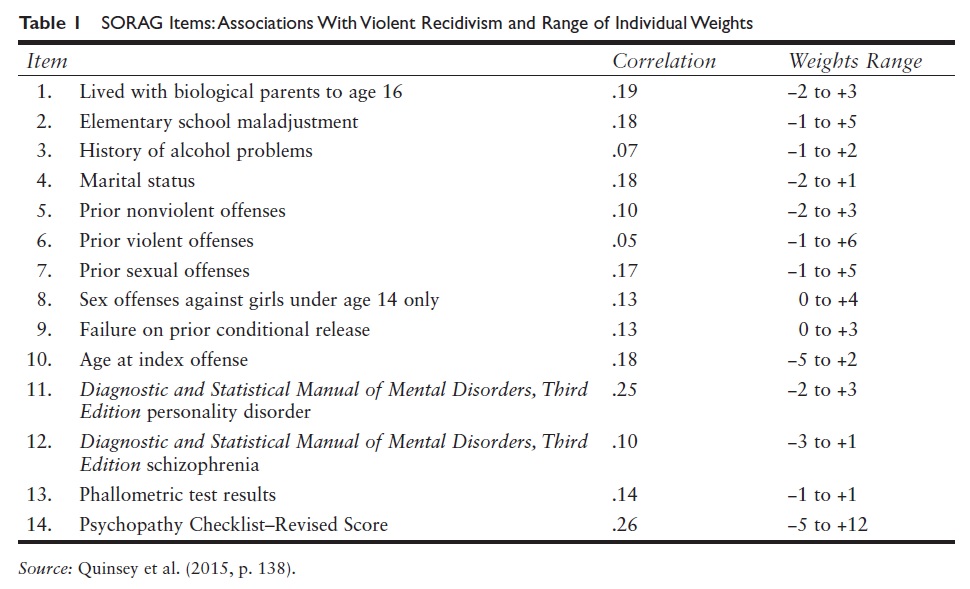

The SORAG was originally developed on 288 adult male sex offenders from four independent samples who were released from Mental Health Centre Penetanguishene and followed up in the community. The rate of violent recidivism observed in the overall sample was 42% over 7 years and 58% over 10 years. The items for the SORAG were identified through statistical procedures aimed at identifying combinations of predictors that optimized the prediction of violence. In all, 14 variables that discriminated violent recidivists from nonrecidivists are listed in Table 1. The correlation for each individual item with binary violent recidivism (i.e., yes–no violently reoffended) is presented in Table 1, along with the weighting of each item.

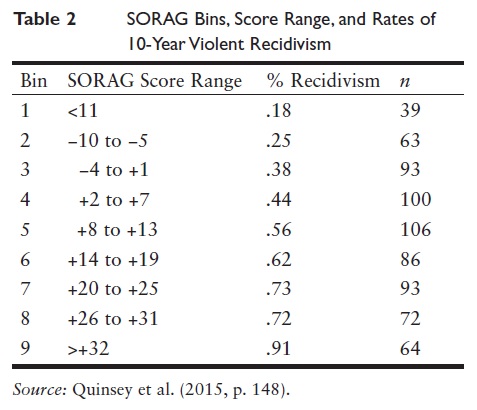

Briefly, correlations are statistics ranging in value from −1.0 to +1.0 representing the strength of association between two variables. When a correlation is computed between one binary variable (i.e., a variable that can take one of only two values, such as inpatient or outpatient or criminally insane or not criminally insane) and another variable with a range of values, this is called a point biserial correlation. Point biserial correlations from .10 to .23 are considered small in magnitude, while those ranging from .24 to .36 are moderate and .37 and above are high. These 14 items were used as the foundation for developing the SORAG. After the best predicting items were identified, a technique known as the Burgess method was used to differentially weight predictor variables shown to successfully discriminate violent recidivists from nonrecidivists. For each category or value of a predictor demonstrating a 5% increase or decrease in recidivism from the overall rate, a weighting of +1 or −1, respectively, is assigned. The weights are increased in either direction based on the degree of difference from the overall recidivism rate associated with a given category or value on a variable. In this manner, stronger predictors—that is, variables with the best discriminating power—were given the heaviest numerical weights (see Table 1). As the SORAG is part of a collection of instruments that were developed in a purely data-driven Once scored, the items are summed to generate an overall score that was associated with the probability of violent recidivism post-release. With possible scores ranging from −26 to +51, the SORAG is scored in a manner such that higher scores were associated with increased violent recidivism and lower scores were associated with lower rates of future violence. The SORAG was then divided into nine score bands which were associated with different rates of violent recidivism over 7-year or 10-year follow-up. In 2013, the SORAG was renormed on a sample of 716 sex offenders with a minimum of 10-year follow-up. With a sample nearly triple the development sample, the bin sizes were also larger and more representative. For instance, Bin 9 in the construction sample had only five cases, while in the updated normative sample, it has 64 cases. Table 2 presents summary information on the nine SORAG risk bins, score range, the percentage of 10-year violent recidivism associated with bin membership, and the bin size (n) for each.

Subsequent Validations

In the original development sample for the SORAG, the instrument demonstrated a strong predictive accuracy for future violence, with an area under the receiver operating curve (AUC) value of .75. With possible values ranging from 0 to 1, an AUC of .75 would be interpreted to mean there is a 75% chance that a randomly selected violent recidivist had a higher SORAG score than that of a randomly selected non-recidivist. Such an effect is considered to be large in magnitude and to represent high predictive accuracy. The authors noted that the SORAG was a weaker predictor of sexually motivated recidivism (being .05 to .15 lower in terms of AUC value), but that it continued to significantly predict this specific outcome.

Subsequent validations of the SORAG have reaffirmed its properties for predicting future sexual and general violence among sex offenders. Quantitative reviews of the SORAG, termed meta-analysis, have been conducted to examine how well the SORAG and its variants predict future violence post-release among sexual offenders. A major meta-analysis published in 2009 of 118 recidivism prediction studies of men who committed sexual offenses generated support for the predictive properties of the tool. Specifically, AUC equivalents (converted from Cohen’s d) were obtained for the prediction of sexual recidivism (AUC = .67, 12 studies), violent recidivism (AUC = .71, eight studies), and general recidivism (AUC = .72, eight studies). In the 2013 renorming of the SORAG on 716 sex offenders, the tool demonstrated very good predictive accuracy for violent recidivism (AUC = .73).

In all, the existing research to date has supported the predictive accuracy of the SORAG scores for the prediction of future sexual violence, general violence, and general criminal recidivism among adult male sex offenders.

Strengths, Limitations, and Applications

The SORAG is a fairly objective risk instrument to score that yields a high level of interrater agreement between independent raters, thus demonstrating high interrater reliability. It also has demonstrated high predictive accuracy overall for general violence among sex offenders and moderate-level accuracy for predicting sexually motivated recidivism. It is used frequently throughout the United States and in several countries internationally for assisting decision makers in making judgments about conditional release (e.g., parole boards) or sentencing (e.g., judges, review boards). As the SORAG is composed entirely of static items (i.e., historical and generally unchanging), however, it cannot assess changes in risk from positive progress made in risk reduction treatment or resulting from other credible change agents (e.g., specialized treatment completion, improvement in supports, major deterioration in health). For this reason, there is justification to supplement the SORAG with other measures that assess dynamic (i.e., changeable) risk markers to inform decisions concerning sentencing or conditional release.

Moreover, the SORAG has received criticism on the basis of its normative sample: violent, mentally disordered, psychiatric patients. Arguments have been advanced that the recidivism rates and the weighting of the items may be less applicable to nonmentally disordered offenders in conventional justice settings (e.g., prison, probation); of note, however, many replications of the SORAG have been with sex offender samples across a range of correctional and forensic settings, supporting the generalizability of its predictive properties. Critics have cited additional concerns, however, with the representativeness and stability of the instrument’s bin structure, for instance, containing some bins of extreme scores with small subgroups of men (e.g., Bin 9) associated with 100% recidivism. The revised 2013 norms address this concern with larger ns, a greater representation within each of the nine risk bins, and none of the bins reaching 100% recidivism, even for the most extreme scores over the longest follow-up periods.

Revision and New Validations

The 2013 renorming of the SORAG also saw the development of a revised tool intended to supplant the SORAG through merging its item content with a companion measure developed by the same research group to form the Violence Risk Appraisal Guide-Revised (VRAG-R). The VRAG-R was developed and validated on a sample of 1,261 violent offenders from previous studies with an extended follow-up and is intended for use with both sexual and nonsexual violent offenders. The VRAG-R is simplified in scoring, including no longer requiring the rating of diagnostic criteria and substituting the antisocial factor from the Psychopathy Checklist-Revised in place of the whole instrument. Validation research for the VRAG-R is promising (AUC = .76), and further research will be forthcoming.

Conclusions

The SORAG is an empirical actuarial risk assessment tool with a strong foundation of validity research supporting its predictive accuracy for general violence and sexually motivated violence with adult male sex offenders. In recent years, it has been merged with the VRAG, and the resulting instrument has been streamlined to create the VRAG-R, which has simplified scoring and demonstrated predictive accuracy for future violence among sexual and violent nonsexual offenders. Although the limitations inherent within any static tool apply no less to the SORAG, the tool enjoys a widespread and an international use to assist decision makers in sentencing and conditional release decisions to manage risk, prevent future violence, and enhance public safety.

References:

- Hanson, R. K., & Morton-Bourgon, K. (2009). The accuracy of recidivism risk assessments for sexual offenders: A meta-analysis of 118 prediction studies. Psychological Assessment, 21, 1–21. doi:10.1037/ a0014421

- Quinsey, V. L., Harris, G. T., Rice, M. E., & Cormier, C. A. (2015). Violent offenders: Appraising and managing risk (3rd ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Rice, M. E., & Harris, G. T. (2016). The sex offender risk appraisal guide. In A. Phenix & H. M. Hoberman (Eds.), Sexual offenders: Diagnosis, risk assessment, and management (pp. 471–488). New York, NY: Springer.