Although legal definitions of sexual offenses vary, the term sexual offending typically denotes offenses whereby an individual engages in unwanted sexual acts with another person who does not give, or is unable to provide, consent. Given the impact such acts have on survivors, sexual offenses receive considerable attention from the media, policy makers, and the criminal justice system. These concerns highlight the need for accurately assessing the likelihood that those who have offended sexually will recidivate or commit future sexual offenses. After reviewing factors associated with risk of sexual reoffending, this article describes assessment techniques commonly used by those conducting risk assessments for sexual offending and outlines the components of a sex offender risk assessment.

Factors Associated With Risk of Sexual Reoffending

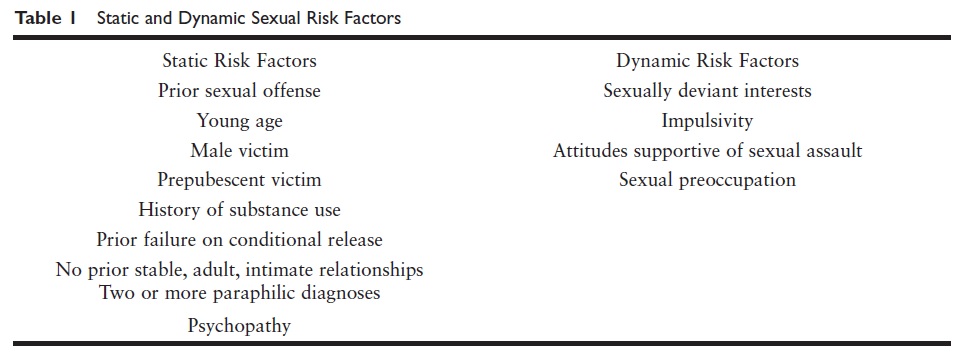

When conducting sex offender risk assessments, evaluators utilize both static and dynamic risk factors. Static risk factors remain constant or cannot be changed by treatment (e.g., the offender’s prior offense history), whereas those factors that may fluctuate are referred to as dynamic risk factors. Some dynamic factors may also be referred to as long-term vulnerabilities or risk-relevant propensities as these factors, while relatively stable, are oftentimes the focus of sex offender treatment programs designed to lessen the offender’s overall risk. See Table 1 for a list of static and dynamic risk factors for sexual risk.

One of the most useful predictors of future behavior is previous behavior, and the same is true when predicting risk of sexual reoffense. Offenders who have previously committed sexual offenses are at a greater risk of sexual recidivism compared to those with nonsexual prior offenses. Additionally, the younger one was at the time of his or her first sexual offense, the greater the risk of future sexual offending. The time span of sexual offending is also associated with risk, with offenders who have a longer sexual offending history being at an increased risk of sexual recidivism. For example, a 30-year-old offender who has been offending sexually since the age of 16 has greater risk of continued offending compared to a 30-yearold offender whose sexual offending history has spanned 5 years.

The offender’s current age is also a determinant of risk of sexual recidivism. Adult offenders under the age of 30 typically have the highest rates of sexual reoffense compared to older offenders. Although the risk of sexual recidivism declines with age, those who offend against children tend to have a slower decline in risk of sexual reoffense over time compared to other types of sexual offenders.

An additional dynamic risk factor for sexual recidivism is the presence of deviant sexual interests. There is some debate regarding how to define sexual deviance, but those who display sexual attraction to prepubescent children are often categorized as demonstrating sexually deviant interests and are thus viewed as having a greater risk of sexual recidivism. Additionally, individuals who derive sexual pleasure from torturing or humiliating their victim or prefer sex that includes force or violence to consensual sex are also considered to be demonstrating deviant sexual interests.

Offenders who derive sexual pleasure from torturing or humiliating a nonconsenting individual may meet diagnostic criteria for the paraphilia sexual sadism. Paraphilias involve fantasizing about, or acting on, sexual interests that are generally considered atypical. Individuals diagnosed with a paraphilia may experience distress or impairment in functioning as a result of their sexual interests. In addition to some paraphilias being reflective of deviant sexual interests, research suggests that offenders diagnosed with two or more paraphilias are at increased risk of reoffending sexually.

Offenders who display attitudes that are supportive of sexual assault, such as the belief that one is entitled to sex, are at an increased risk of sexual offending. Being preoccupied with sex is also associated with an increased risk of sexual offending. Indicators of preoccupation with sex include the belief that one has a stronger sexual drive than others and placing an inflated level of importance on sexual behavior compared to other parts of one’s life. How frequently one views pornographic material, engages in sexual behavior, or fanaticizes about sexual acts can also be indicators of sexual preoccupation. Sexual preoccupation may also negatively impact an offender’s personal relationships, with research indicating that those who have no current or prior intimate relationships with another adult are at an increased risk of sexual reoffense.

Sexual offenders who display antisocial traits, such as impulsivity and a disregard for social norms, are also at an increased risk of sexual recidivism. Failure to adhere to treatment or supervision requirements is oftentimes indicative of antisocial tendencies, with offenders who leave treatment prematurely or fail to abide by supervisory requirements being at an increased risk of sexual recidivism. Although the relevance of antisocial tendencies to risk of reoffense is true for sex offenders in general, those who sexually offend against adults are more likely to exhibit antisocial traits than those who offend against children.

Another risk factor for sexual reoffense, psychopathy, is also more prevalent in those who offend against adults versus those who offend against children. Psychopathy constitutes a personality construct that includes interpersonal, emotional, and behavioral traits. Individuals classified as psychopathic may show traits such as lack of remorse or empathy, poor behavioral controls, and sexual promiscuity. In addition to being associated with risk of violent offending, those who are classified as psychopathic are also more likely to engage in sexual recidivism compared to those who are not considered psychopathic. A final risk factor more commonly seen in those who offend against adults is substance use diagnoses, with those who have a history of abusing substances being at a greater risk of sexual recidivism.

Victim demographics are also associated with risk of sexual recidivism. Sexual offenders who offend against males or unrelated victims pose a greater risk of sexual recidivism than those who offend against females or those known to them. Additionally, individuals who offend against various types of victims (e.g., males and females, adolescents and adults) pose a greater threat for reoffense compared to offenders who only offend against a singular type of victim.

Sexual Recidivism Risk Assessment Instruments

Various instruments have been designed to assess the risk of sexual recidivism and provide evaluators with more objective methods of assessing risk of sexual recidivism. Although these measures differ with regard to how risk is conceptualized and measured, a 2009 meta-analysis by R. Karl Hanson and Kelley E. Morton-Bourgon suggested that sex offender risk assessment instruments have similar levels of predictive accuracy. Given findings of similar predictive accuracy across leading measures, the decision regarding which instrument to employ often rests on selecting an approach to estimating sexual recidivism that best fits with the purpose of the evaluation.

For example, evaluators seeking to identify changes in an offender’s risk over time may choose a structured professional judgment instrument that includes static and dynamic factors. Structured professional judgment s may also include protective factors, or those that reduce an offender’s overall risk, and identify relevant risk factors to consider while allowing for professional judgment when making the final risk determination. The Sexual Violence Risk-20 is considered an structured professional judgment and includes 20 items that address the offender’s criminal history, psychosocial functioning, and future plans. This instrument allows evaluators to classify the offender’s overall risk and prioritize the types of interventions for the offender.

The STATIC-2002R is an example of an actuarial instrument or instrument that arrives at a final risk score and risk estimate based on a mathematical formula. The current version of the instrument contains 14 items that cover information about the offender’s age, sexual offending and general criminal history, deviant sexual interests, and victim characteristics. The scores from the individual items are summed to obtain a final score of risk that corresponds to a risk classification level ranging from low to high in likelihood for sexual reoffense over 7 and 10 years. Although this instrument provides long-term recidivism estimates and relies on empirically supported items, some express concern that the instrument does not show changes in risk of sexual reoffense given the sole reliance on static variables.

A final group of risk assessment instruments is referred to as mechanical instruments and is similar to actuarials in that instructions are provided for what risk items to consider and how to combine the factors to arrive at a risk estimate. Unlike actuarials, mechanical instruments do not provide information for how the final risk estimates relate to recidivism rates. An example of a mechanical instrument is the Sex Offender Treatment Intervention and Progress Scale, which includes 16 dynamic risk items related to the offender’s sexual deviance, general criminal behavior, and interpersonal relationships. Total scores are categorized into three levels of risk, with research suggesting that the instrument is reliable and moderately predicts risk of sexual recidivism.

Additional Assessment Measures

Evaluators may also utilize assessment procedures, such as the penile plethysmograph (PPG), that measure physical responses to stimuli as a strategy to evaluate sexual risk. Although a version is available for use with females, the version designed for use with males has been researched extensively and is the focus of the description that follows. The PPG is administered by having the male place an apparatus on his penis, termed a circumferential strain gauge, that measures fluctuations in penile circumference or volume in response to audio or visual sexual stimuli (e.g., narratives, images) that depict male and female adults and children. Fluctuations in penile volume or circumference are purported to be indices of sexual arousal that are associated with sexual recidivism. For example, an offender who displays arousal in response to images of female children can be inferred to be at greater risk of offending against female children than an offender who does not display a pattern of arousal in response to these stimuli.

Although some research suggests that the PPG effectively assesses risk for those who offend against children, there are several concerns regarding the use of the instrument. First, the obvious nature of how the instrument assesses risk can result in offenders distorting their results. Individuals could deliberately imagine stimuli other than the images presented to interfere with the validity of test results. Additionally, research suggests that males can control penile volume so that the presence, or absence, of arousal may be unrelated to the images that the individual is viewing. Because of these concerns, and the intrusiveness of the procedure, evaluators may opt to utilize another physiological measure when assessing sexual risk.

Gene Abel and associates developed the Abel Assessment for Sexual Interest to assess sexual preference. The Abel Assessment requires individuals to first complete a questionnaire regarding deviant sexual interests, sexual history, and criminal history. They then view a series of 160 digital images depicting individuals who are clothed in bathing suits and vary with regard to age, gender, and ethnicity. Offenders are asked to initially view each image and then go through the images a second time to rate their level of sexual arousal in response to each picture. In addition to obtaining a measure of the individual’s reported arousal to each image, the amount of time spent viewing each image is recorded.

The assumption behind the Abel Assessment is that the length of time spent viewing stimuli is indicative of the level of sexual arousal one experiences in response to the images. Although this instrument has been shown to have similar predictive utility as the PPG when detecting those who offend against children, there is concern that without a direct measure of sexual arousal, one cannot assume that the length of interest shown in a type of image is necessarily indicative of sexual arousal.

Conducting the Evaluation

Evaluations of sexual risk often assist in determining an appropriate sentence, whether an offender meets criteria to be labeled as a sexually violent predator, and to inform treatment recommendations or management strategies to prevent continued sexual violence. When evaluating risk of sexual recidivism, evaluators should be aware of the limitations of certain assessment methods and applicability of specific assessment instruments to ensure selecting the best assessment approach for a given evaluation. For example, some assessment procedures (e.g., PPG) work more effectively with those who offend against children and, thus, may be less suitable for evaluating those with no known history of offending against children. Demographic characteristics may also influence which instrument is appropriate as many risk assessment instruments were designed for use with males, which limits their applicability when evaluating risk of a female sexual offender. There is also concern that the more commonly used sex offender risk assessments may not accurately assess risk for offenders who display symptoms of a major mental illness or diagnosis of intellectual disability, and it is important that evaluators convey any limitations to their assessment strategy within their report.

Review of Available Records and Collateral Sources

Records are considered to be the cornerstone of any forensic evaluation and the same is true of evaluations for sexual violence risk. An offender’s criminal history, including police reports, should be obtained as these documents provide information regarding the offender’s offense history, prior compliance with supervision requirements, and victims’ demographic information. If an offender is currently incarcerated or in a psychiatric facility, records from the facility can assist in determining whether the offender is displaying active mental health symptoms and whether he or she has complied with supervision requirements.

Mental health records are also used to determine the presence of psychiatric diagnoses related to risk of reoffense and whether the offender has complied with, or benefited from, previous attempts to manage mental health symptoms. Evaluators should obtain previous risk assessments, if available, as these records may contain additional information regarding the offender’s offending patterns and responsivity to treatment as well as serve as a comparison point to determine any fluctuations in risk of sexual recidivism. Additional records, or collateral sources, may include school records, child protective agency records, interviews with family members, or interviews with previous treatment providers. It is preferable to review records before interviewing the offender as information contained in the records can assist the evaluator select relevant lines of inquiry and provide the necessary knowledge for asking follow-up questions should an offender provide information that contradicts available records.

Interview

The types of questions asked during the interview may depend on the reason for the evaluation. For example, if conducting a sexually violent predator evaluation, the evaluator must address factors outlined in statutes, which influences the degree to which certain areas are covered during an interview. Although the information emphasized during an interview may vary depending on the reason for the evaluation, evaluators typically gather information regarding the offender’s background, mental health history, and criminal history. An offender’s background can aid in identifying patterns of behavior as well as the onset of mental health diagnoses or substance use. Evaluators question offenders about mental health symptoms to determine whether there is evidence to warrant a mental health diagnosis that has been previously undiagnosed. Questions regarding the offender’s sexual offending history and their history of sexual functioning in general is relevant, as it can provide information about the potential for sexual preoccupation or a preference for nonconsensual sex.

Utility of Standardized Risk Assessment Instruments

Evaluators should utilize a standardized risk assessment instrument, such as those reviewed herein. Although the record review and interview provide important information about the presence of risk factors, a standardized risk assessment instrument provides a more objective evaluation of risk of sexual recidivism and is considered necessary during a risk assessment. There is a large number of instruments available to assess risk of sexual recidivism, and it is important that evaluators weigh relevant factors to determine which instrument is most appropriate for the evaluation.

Future Research

Although significant advances have been made in predicting risk of sexual recidivism, additional research is required to determine whether current practice accurately predicts risk of sexual violence for specific groups (e.g., female sex offenders) and the extent to which available instruments accurately predict risk of sexual recidivism. This research will help ensure that evaluators are conducting evaluations that align with ethical guidelines and standards of practice.

References:

- Beech, A. R., Craig, L. A., & Browne, K. D. (2009). Assessment and treatment of sex offenders: A handbook. West Sussex, UK: Wiley.

- Craig, L. A., Browne, K. D., & Beech, A. R. (2008). Assessing risk in sex offenders: A practitioner’s guide. West Sussex, UK: Wiley.

- Hanson, R. K., & Morton-Bourgon, K. E. (2009). The accuracy of recidivism risk assessments for sexual offenders: A meta-analysis of 118 prediction studies. Psychological Assessment, 21, 1–21. doi:10.1037/ a0014421

- Saleh, F. M., Grudzinskas, A. J., Bradford, J. M., & Brodsky, D. J. (Eds.). (2009). Sex offenders: Identification, risk assessment, treatment, and legal issues. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Smid, W. J., Kamphuis, J. H., Wever, E. C., & Van Beck, D. J. (2014). A comparison of the predictive properties of nine sex offender risk assessment instruments. Psychological Assessment, 26, 691–703. doi:10.1037/a0036616