The Violence Risk Appraisal Guide (VRAG) and the Violence Risk Appraisal Guide-Revised (VRAG-R) are actuarial instruments designed to estimate the likelihood with which a male criminal offender or forensic psychiatric patient will be charged for at least one new violent offense within a 7- or 10-year period of opportunity to reoffend. Opportunity to reoffend is defined by community access, and violent offending is defined to include hands-on sex offenses. An actuarial instrument derives a probability of a future event’s occurrence by tabulating the frequency with which the event has occurred in the past among individuals from a similar population.

Many decisions about offenders in the criminal justice and forensic psychiatric systems are dependent on formal or implicit appraisals of risk—most importantly, in terms of community safety, the risk of an offender committing new violent or sexual offenses. Risk appraisal is therefore relevant to granting bail, sentence length, amount of supervision on parole and probation, release to the community, and assignment to institutions varying in level of security. As with a number of actuarial instruments, the VRAG and the VRAG-R were designed to assist in the determination of the degree of risk posed by individual offenders.

The VRAG

In the case of the VRAG, offenders were followed after release from incarceration and the frequency with which they committed additional violent or sexual crimes was noted. Prerelease characteristics of these offenders were then related to whether they had committed a new violent or sexual offense. The characteristics that were most highly related to recidivism were combined to yield a single score that could be used to estimate the probability of violent/sexual reoffending in new cases.

VRAG Items

The VRAG comprises the following items:

- Revised Psychopathy Checklist score (a rating instrument devised by Robert Hare to measure psychopathic personality traits such as callousness and duplicity)

- Elementary School Maladjustment score

- meets psychiatric criteria for any personality disorder

- age at time of the index offense (negatively related to recidivism)—the index offense is the offense leading to institutionalization or referral

- separation from either parent (except death) under age 16 years

- failure on prior conditional release

- nonviolent offense history

- never married (or equivalent)

- meets psychiatric criteria for schizophrenia (negatively related to recidivism)

- most serious victim injury in index offense (negatively related to recidivism)

- alcohol abuse score

- female victim in index offense (negatively related to recidivism)

The items were selected from a larger pool based on their relationship to violent recidivism rather than on theoretical or commonsensical ideas, so they may seem counterintuitive. The negative relationship between schizophrenia and violence risk is an exemplar of such an apparently anomalous result. The reason for this negative relationship becomes apparent on reflection: In studies of the general population, schizophrenia and other major mental disorders are modest risk indicators but are much poorer risk indicators than diagnoses of personality disorder, sexual deviance, and substance abuse. Thus, when a sample of offenders is studied, schizophrenia appears to be a protective factor because those with schizophrenia are being compared to a group composed largely of offenders who are personality disordered, paraphilic, and/or substance abusing. Similar considerations apply to some of the other items. Murderers have, on average, lower rates of violent recidivism than a group of unselected offenders; offenders who have female victims do not contain homosexual pedophiles (who have high rates of sexual recidivism). Part of the issue with both murderers and offenders with female victims is that a substantial proportion of both groups committed their admission offense against their spouse and such individuals tend to have low rates of violent recidivism.

Some readers may point to exceptions to the assertions in the preceding paragraph, such as domestic murderers who turned out to be serial killers or serial rapists (of women). Two considerations temper the force of these objections. The first (and weaker) is that the instrument deals in probabilities not certainties. Second, and more importantly, the items work together, rather than in isolation. It is the combination of items (e.g., a pattern of early antisocial behavior coupled with an adult offense) that yields a high-risk score. The VRAG is in part a measure of the persistence of antisocial and criminal behavior across the life span. In the end, however, it is not theoretical ideas, commonsense notions, or anecdotes derived from one’s personal experience or reading that count but only the empirical relationship between the actuarial measure and outcome.

Principal Results

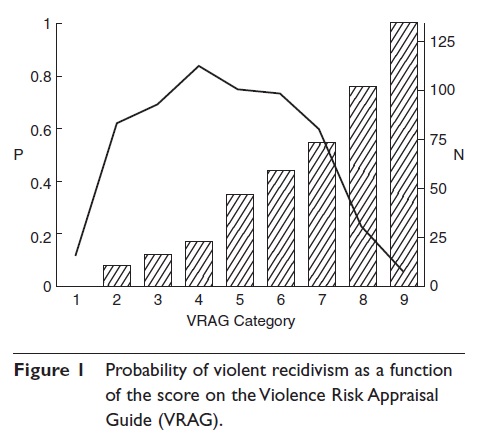

Data from the original sample of 618 offenders are shown in Figure 1. Each offender had been assessed or treated at a maximum-security psychiatric facility in Ontario, Canada; most of the assessed-only offenders were subsequently sentenced to correctional facilities before their release. VRAG scores are divided into nine equal-sized ranges (bins), and the probability of violent recidivism is shown by the height of the bar for each bin. The line denotes the number of offenders in each bin. Figure 1 shows the linear relationship between VRAG score and the likelihood of violent reoffending and that relatively few individuals receive very high or low scores.

Accuracy of Prediction

The measurement of predictive accuracy is complex and has sometimes been controversial, although in 2015, there is a consensus among statisticians about what methods should be used and how the results of these should be interpreted. Actuarial methods are used for prediction and evaluated similarly in many areas, such as medicine and the insurance industry. One simple way of indexing predictive accuracy is to calculate the likelihood that a randomly sampled individual from one outcome group (in this case, violent recidivists) will have a higher score on a predictive instrument than a randomly sampled individual from the other group (those not committing such offenses). This probability in the case of the VRAG is approximately .75, indicating sufficient accuracy to be useful in practical decision-making about release and supervision for individual offenders. It is important to understand that an actuarial instrument (or any other method of prediction) is less useful when applied to a population in which the base rate of the phenomenon to be predicted is very high or very low. This would occur in the case of the VRAG where almost all or almost no offenders in a particular population committed new violent offenses. Thirty-one percentage of offenders in the original sample were violent recidivists in 7 years at risk.

The accuracy of the VRAG compares favorably with other methods of predicting violent reoffending. It has long been known that mental health professionals, including experienced forensic psychologists and psychiatrists, show poor agreement among themselves in predicting violent recidivism, overpredict its occurrence, and are less accurate than actuarial instruments. The accuracy of clinicians can be improved by structuring their judgment with standardized rating scales or checklists, although research indicates it usually falls short of that obtained with actuarial instruments such as the VRAG. Neither professional judgment nor structured discretion methods yield an actual probability of violent reoffending. However, the absolute probability of reoffending is not critical for all types of decisions. For example, forensic or correctional administrators may have fixed budgets for treatment or supervision and may wish to differentially provide these to higher risk cases. Relative risk, as indexed by the percentile rank of the offender on the VRAG, is appropriate for this type of decision.

Replications

Since the VRAG was introduced in the 1990s, there have been about 60 replications around the world, most of which were conducted by individuals unconnected with the VRAG authors. The VRAG, like most actuarial instruments, is robust upon replication: For example, accuracy in predicting violent recidivism in the community in six studies conducted by the VRAG authors averaged .73 and averaged .72 in 20 replications conducted by others.

The VRAG-R

The VRAG-R, first published in 2013, was developed primarily to simplify the VRAG scoring system. The VRAG-R correlates highly with the VRAG and has nearly identical accuracy of prediction. Because the VRAG-R is easier to score, the developers of the VRAG and VRAG-R recommend use of the latter.

The sample of 1,261 offenders used for its construction included the offenders used to develop the VRAG. The VRAG-R has 12 items, each scored or weighted according to the direction and magnitude of its relationship to violent (including sexual) reoffending, and then summed to obtain a total score. The items are historical (static) in nature and do not change with time, unless there is a new offense and the offender is reassessed.

VRAG-R Items

The VRAG-R items comprise the following:

- lived with both biological parents to age 16 years (negatively related to recidivism)

- elementary school maladjustment

- history of alcohol or drug problems

- marital status at time of index offense

- charges for nonviolent offenses prior to index offense

- failure on conditional release from corrections

- age at index offense (negatively related to recidivism)

- charges for violent offenses before index offense

- n umber of prior admissions to correctional institutions

- conduct disorder before age 15 years

- sex offending

- antisociality: poor behavioral controls, early behavioral problems, juvenile delinquency, revocation of conditional release, criminal versatility

The items are designed to be scored from information contained in the offender’s file: a detailed psychosocial history or parole/probation assessment, psychological and psychiatric assessments, court records, criminal history, and psychiatric history. Given adequate information, it is not necessary for the assessor to interview the offender to complete the assessment. To the degree possible, information from multiple sources is used. It is particularly important for assessors to corroborate information obtained from offender self-report. When there is missing information for a particular item, it can be prorated (estimated) according to a formula. Up to 4 items can be prorated to obtain a valid score. Trained raters show extremely close agreement when independently scoring the same file.

The Nature of Static Risk

The VRAG-R is designed to predict the occurrence of at least one violent re-offense in a lengthy period of opportunity. Intervals of opportunity ranging from 6 months to 49 years have been examined and the VRAG-R performs well in all of them. The predictions in all cases were made at the time the offender was assessed subsequent to the commission of the index offense, thus changes in the offender that may have occurred during institutionalization or post-release were not considered. It is the case, however, that offenders are slightly less likely to reoffend with each year of opportunity to reoffend they complete without reoffending. There is a formula to compute this reduction in risk. Time spent in forensic or correctional institutions after assessment, however, does not reduce risk.

Theoretical Interpretation

The principal implication of the results of the research leading to the development of the VRAG-R is the concrete demonstration of the large variation in risk of violent reoffending posed by different offenders.

The VRAG-R items are individual-level correlates of crime, most of which have been extensively documented in many societies throughout the world. They are part of a larger class of variables sometimes termed universal correlates of crime. Individual correlates are distinguished from aggregate correlations. Aggregate data are collected at the country, region, or census track level—for example, one can compare the overall crime rates among different countries or correlate the association between income disparity and crime in a particular jurisdiction. Correlations based on aggregate data are often different than correlations based on individual data. There is, for example, a strong association between poverty and crime at the aggregate level but a weak association between poverty and crime at the level of individuals. This particular difference may exist simply because most poor people do not commit crimes, although other factors also contribute. Knowing an offender’s socioeconomic status, therefore, does not help one in forecasting the likelihood of a particular offender’s recidivism.

The items of the VRAG-R were selected empirically based on their success in predicting violent recidivism, not for theoretical reasons, and therefore do not in themselves constitute a theory of violent offending. The success of the instrument, a result of the lawfulness of violent offending, does have theoretical relevance; however, in that, it constitutes data to be explained by a successful theory.

The Future

The developers of the VRAG-R and most other actuarial methods designed to predict recidivism of various kinds hope that their instruments will become obsolete with the development of more effective interventions. With a perfectly effective intervention, the only information pertaining to risk a decision maker would need is knowledge of whether the offender received the intervention. More realistically, if a particular intervention had been shown to reduce the likelihood of violent reoffending by a certain amount, that amount could be incorporated into the actuarial estimate of risk via a simple formula. Alternatively, a measure of response to intervention could be developed that could be used in similar fashion. At present, this desired objective has not yet been met. Although there are some treatments or interventions for offenders that have been shown to reduce criminal recidivism, none demonstrate convincingly that the likelihood of violent or sexual reoffending among high-risk adult offenders can be reduced to the extent that it need be reflected in an actuarial prediction method.

A great deal of program development work and rigorous evaluation will be required before the receipt of or response to intervention can be used to modify actuarial estimates of risk.

References:

- Harris, G. T., Lowenkamp, C. T., & Hilton, N. Z. (2015). Evidence for risk estimate precision: Implications for individual risk communication. Behavioral Sciences and the law, 33, 111–127. doi:10.1002/bsl.2158

- Harris, G. T., & Rice, M. E. (2013). Bayes and base rates: What is an informative prior for actuarial violence risk assessment? Behavioral Sciences and the Law, 25, 951–965.

- Harris, G. T., Rice, M. E., & Quinsey, V. L. (2010). Allegiance or fidelity? A clarifying reply. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 17, 82–89. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01197.x

- Harris, G. T., Rice, M. E., Quinsey, V. L., Lalumière, M. L., Boer, D., & Lang, C. (2003). A multi-site comparison of actuarial risk instruments for sex offenders. Psychological Assessment, 15, 413–425.

- Harris, G. T., Rice, M. E., Quinsey, V. L., & Cormier, C. (2015). Violent offenders: Appraising and managing risk (3rd ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Imrey, P. B., & Dawid, A. P. (2014). A commentary on statistical assessment of violence recidivism risk. Statistics and Public Policy, 2, 1–18. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/2330443X.2015.1029338

- Quinsey, V. L., Jones, G. B., Book, A. S., & Barr, K. N. (2006). The dynamic prediction of antisocial behavior among forensic psychiatric patients: A prospective field study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 21, 1539–1565.

- Quinsey, V. L., & Maguire, A. (1986). Maximum security psychiatric patients: Actuarial and clinical prediction of dangerousness. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 1, 143–171. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1177/088626086001002002

- Rice, M. E., & Harris, G. T. (2014). What does it mean when age is related to recidivism among sex offenders? Law and Human Behavior, 38, 151–161. doi:10.1037/lhb0000052

- Rice, M. E., Harris, G. T., & Lang, C. (2013). Validation of and revision to the VRAG and SORAG: The

- Violence Risk Appraisal Guide-Revised (VRAG-R). Psychological Assessment, 25, 951–965 doi:10.1037/ a0032878