The Violence Risk Scale (VRS), developed by Stephen Wong and Audrey Gordon, is a forensic risk assessment tool designed to assess the risk of violence, identify treatment targets for violence reduction treatment, assess an individual’s readiness for treatment, and evaluate treatment progress and posttreatment level of risk. Forensic risk assessments are widely used in clinical, forensic, and correctional practices and offender management. The VRS has been referred to as a treatment-friendly risk assessment tool because, unlike tools with only historic or static predictors that are not amenable to change, the VRS uses dynamic risk predictors that can change with time or treatment. Thus, the VRS integrates the tasks of violence risk assessment and treatment guidance within the same tool. This article describes the structure and organization of the VRS including its application to different forensic populations together with supporting research evidence.

Using Static and Dynamic Predictors to Assess Change in Risk

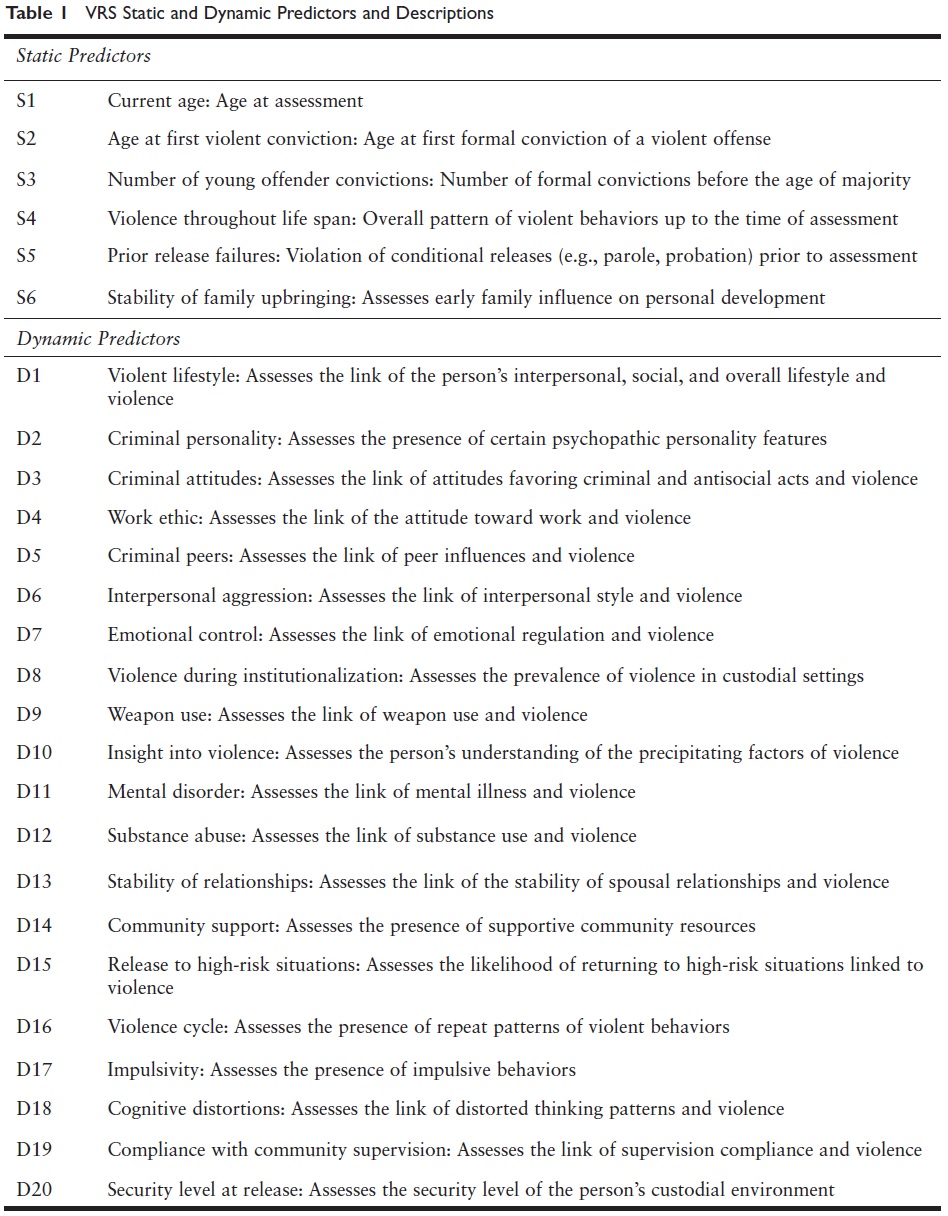

To predict risk of violent reoffending, the VRS uses six static and 20 dynamic predictors (Table 1) that are empirically or theoretically linked to violence or reoffending. The predictors were derived from the widely used Risk-Need-Responsivity principles and an extensive review of the risk assessment and treatment literature.

Detailed descriptions of the static and dynamic predictors and rating instructions are provided in the VRS manual. The VRS dynamic and static predictors are rated on a 4-point scale (0, 1, 2, or 3); higher ratings (2 or 3) indicate the predictors in question are closely linked to violence in the person’s overall functioning. According to the Need principle, dynamic VRS predictors (e.g., substance abuse) rated 2 or 3 that are closely linked to violence should be considered as the person’s treatment targets or criminogenic need areas. The likelihood of future violence could be reduced by providing suitable treatment to the person’s profile of criminogenic needs (i.e., all dynamic predictors rated 2 or 3) according to the Risk-Need-Responsivity principles. Risk predictors rated 1 represent low-risk areas, and predictors rated 0 are considered areas of strength. The VRS total score, which is the sum of the static and dynamic predictors ratings, indicates the person’s overall level of violence risk; the higher the score, the higher the risk. According to the Risk principle, higher VRS scorers are more likely to recidivate than lower VRS scorers and should be provided with more intensive intervention. A clinical override, for example, when a high-risk individual is deemed to be at low risk because of a serious physical disability, is also provided to accommodate exceptional situations not captured by the VRS risk predictors.

Measuring Treatment Change and Change in Risk

The VRS change rubric uses a modified stages of change (SOC) model to assess the person’s treatment readiness and changes in risk during treatment based on a variation of the work of James Prochaska and colleagues. The SOC model, supported by extensive research evidence, posits that treatment improvements tend to progress through a number of stages: the precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance stages. The precontemplation stage is characterized by denial and refusal to acknowledge problems. The contemplation stage is characterized by acknowledging the problems, but no action is taken to change—only talking the talk. Preparation is the contemplation stage plus taking small steps to make relevant change. Action is acknowledging problems plus taking consistent action to make relevant changes. The maintenance stage is the action stage coupled with successfully generalizing changes to many different situations. Changes are relevant if they are expected to reduce the risk of reoffending. For example, if the person has a substance use problem but, for this person, substance use has not been linked at all to offending, treatment of substance use, though beneficial, will not be risk reducing, and refraining from using substances is not a relevant change for risk reduction. The VRS provides operational descriptions for each stage to inform treatment providers what risk behaviors and change behaviors to look for during treatment. Progression from one stage to a subsequent stage is an indication of treatment improvements.

Progression from any one stage to the next stage can be translated into a 0.5-point reduction in the pretreatment risk rating; progression through two stages, a 1-point reduction; and progression through three stages, the maximum progression, a 1.5 reduction. No risk reduction is recorded for progress from the precontemplation to the contemplation stage since no behavioral improvement has taken place, only verbal acknowledgment of problems. For every dynamic risk predictor targeted for treatment, the pretreatment risk rating minus the change score is the posttreatment risk rating for that dynamic predictor. The posttreatment risk is the posttreatment dynamic total score plus the static total score; the latter, in most cases, should remain unchanged. Administration of the VRS is detailed in the VRS manual.

Matching Treatment Strategy to SOC

According to the SOC model, treatment is most effective when it matches the person’s stage of change or readiness for treatment. Assessment of SOC can inform the therapist’s choice of the preferred treatment approach. For someone denying any problems (precontemplation), motivational work and building therapeutic alliances are critical. Actively supporting change and maintaining motivation are particularly important during the preparation stage. Those in the action stage can be provided with increasingly more opportunities to practice their newly learned skills.

Applications to Different Populations

The VRS has been applied to many offenders/service users groups in criminal justice and forensic mental health systems including those diagnosed with major mental illnesses, males and females, aboriginal and non-aboriginal offenders, offenders in prison and released on parole in the community, high-risk violence-prone offenders, and offenders with psychopathic and antisocial personality features. Various studies have indicated that the psychometric properties of the VRS such as interrater reliability, internal consistency, predictive, and concurrent validity are acceptable to good.

Violence Prediction Validity

The majority of criminal justice and forensic mental health work typically requires making reoffending predictions, in particular, violent reoffending predictions. Violent reoffending has a lower base rate or frequency of occurrence than nonviolent or generally reoffending and, therefore, is more difficult to predict. The predictive validity of the VRS can be evaluated by first assessing a target group using the VRS, tracking them for a period of time in the community when they have opportunities to reoffend, and determining the number of persons who reoffended. The association of VRS scores and reoffending can be determined statistically, for example, using correlation coefficients or area under the curve as estimates of the magnitude (i.e., effect size) of the association. A substantial and statistically significant association between VRS scores and violent reoffending could be considered as evidence of the predictive validity of the VRS.

The predictive validity of the VRS has been demonstrated in all the offender and service user groups mentioned previously. Most risk prediction tools can predict violent reoffending at a medium level, that is, one with a medium effect size which can be measured by a statistic such as a correlation coefficient or the area under the curve. For example, an area under the curve of about .56, .64, and .71 are often referred to as low, medium, and high effect size, respectively. The predictive efficacy of the VRS varies from medium to high depending on the sample in question. VRS can predict both violent and nonviolent reoffending at various time periods post- assessment (i.e., from 1 year to over 4 years) after release to the community. Dynamic predictors were found to predict just as well as static predictors. The predictive efficacy of the VRS is expected to be lower when the tool is applied to a more homogenous group of offenders such as a group of high-risk and high-psychopathy offenders. For such a group, the VRS predictive efficacy is medium but still statistically significant. Samples that are more homogenous (i.e., with a smaller spread or a restriction of range of the group’s defining characteristics) are more difficult to discriminate than a less homogeneous group. For these reasons, the predictive efficacy of the VRS is smaller (medium effect size) for a group of high-risk and high-psychopathy offenders (more homogenous) compared to that of an average group of offenders who are less homogenous (medium to high effect sizes).

Assessing Treatment Change and Reoffending

The VRS was also designed to assess risk changes such as changes over time or after risk reduction treatment. To assess change, risk has to be assessed at two or more time points, such as pre- and posttreatment or Times 1, 2, and 3. To determine that the purported risk changes are, in fact, risk related and not a measure of some spurious change, the assessed change must be significantly linked to predicted changes in recidivism. If VRS change scores could be shown to be significantly associated with reduction in reoffending, then such findings could be taken as evidence that the VRS could reliably and validly assess risk change. Risk change research is still at an early stage of development and much more research in this area is required. Very few risk assessment tools have provided empirical evidence that risk changes assessed at 2 or more time points are linked to predictable changes in reoffending.

In a 2012 study with a sample of high-risk and psychopathic offenders who had participated in a risk reduction treatment program, risk reduction assessed with the VRS pre- and posttreatment was significantly associated with reduction of violent reoffending in the community. Such associations remain statistically significant after controlling for various potential confounds such as pretreatment risk level, psychopathy, ethnicity, length of follow-up time, and time from end of treatment to community release. The increasing body of research evidence indicates that the VRS is a psychometrically sound risk assessment tool that can be used to assess and predict violent and nonviolent reoffending as well as to assess risk changes.

References:

- Lewis, K., Olver, M., & Wong, S. C. P. (2012). The Violence Risk Scale: Predictive validity and linking changes in risk with violent recidivism in a sample of high risk offenders with psychopathic traits. Assessment, 20(2), 150–164.

- Wong, S. C. P., & Gordon, A. (2006). The validity and reliability of the Violence Risk Scale: A treatment friendly violence risk assessment scale. Psychology, Public Policy and Law, 12(3), 279–309

- Wong, S. C. P., Gordon, A., & Gu, D. (2007). The assessment and treatment of violence prone forensic persons: An integrated approach. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 190, s66–s74.

- Wong, S. C. P., & Olver, M. (2010). The Violence Risk Scale and the Violence Risk Scale-Sex offender version: Two treatment- and change-oriented risk assessment tool. In R. Otto & K. Douglas (Eds.) (pp. 131–156), Handbook of violence risk assessment. Milton Park, UK: Routledge.