The Structured Assessment of Violence Risk in Youth (SAVRY) is one of the most widely used and researched structured risk assessment tools designed to assess risk of general violence in male and female youth between the ages of 12–18 years. The SAVRY is particularly relevant to the topic of correctional psychology, given its applicability to the assessment and management of risk in adolescent offenders. The current entry describes the SAVRY and briefly discusses its purpose and development, then provides a broad overview of empirical findings regarding its reliability and validity.

Description and Purpose of the SAVRY

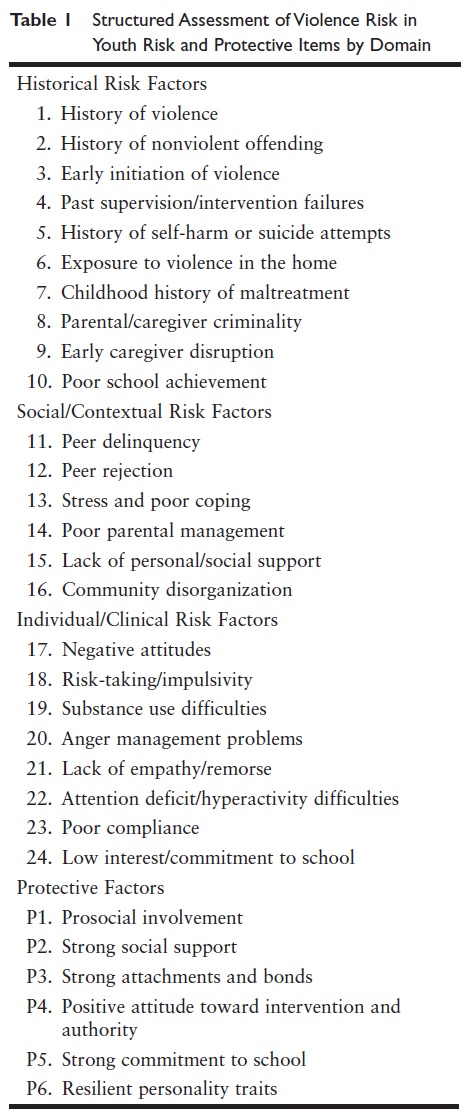

The SAVRY consists of 30 items (i.e., 24 risk factors; 6 protective factors) that are grouped into three risk domains, Historical Risk Factors, Social/ Contextual Risk Factors, and Individual/Clinical Risk Factors, and one protective domain, Protective Factors. Items are operationally defined within the SAVRY manual with the risk factors being rated as low, moderate, and high, whereas the protective factors are rated dichotomously as present or absent. However, given that the SAVRY is not an exhaustive list of risk/protective factors, an assessor may take into consideration other individual or situational factors (i.e., case-specific factors) that may contribute to or mitigate an adolescent’s risk of violence (i.e., Additional Risk Factors/Additional Protective Factors). Moreover, an assessor may judge a risk or protective factor as being particularly salient with respect to a youth’s level of violence risk and may, therefore, identify such factors as critical items. Table 1 lists the items of the SAVRY by domain.

The SAVRY is intended to be administered as part of a comprehensive forensic assessment, and scoring of the items takes approximately 10–15 min once information has been gathered. The overall purpose of the SAVRY is to help guide the assessment and management of violence risk. Given that adolescence is a time of rapid developmental change, the SAVRY was developed to account for the dynamic and contextual nature of adolescent violence, while also providing developmentally informed risk and protective factors (e.g., poor parental management). To increase its flexibility, the SAVRY adheres to the structured professional judgment approach to risk assessment in that a final score is not produced by summing the item ratings; rather the assessor, based on his or her consideration of the risk and protective factors and his or her own professional expertise, generates a final determination regarding the nature and severity of a youth’s risk of future violence using a summary risk rating of low, moderate, or high. An additional summary risk rating can be made using the SAVRY regarding future risk of nonviolent offending due to the overlap between risk factors for violent and nonviolent offending. Although no final risk score is produced in practice, much of the research conducted with the SAVRY has used total scores derived by summing the risk factors to produce a risk total score and/or by summing the factors across the various domains. Whereas the likelihood for violent reoffending typically increases as a function of the number of risk factors present, not all youth who exhibit a wide range of risk factors are to be automatically considered high risk. This is due to the weighting of the SAVRY items being determined by the assessor based on their relevance to the individual case (i.e., the identification of critical items). Lastly, while the SAVRY does include static (i.e., historical) risk factors, approximately two thirds of the risk factors are potentially dynamic (i.e., changeable), and the authors (Randy Borum, Patrick Bartel, and Adelle Forth) recommend that youth be reassessed at regular intervals particularly in situations in which transitional (e.g., transfer from custody to the community) and/or developmental changes are occurring, though no specific time frame has been provided.

Development of the SAVRY

Development of the SAVRY began in 2000, when Borum, Bartel, and Forth amalgamated items from two independently developed risk assessment tools still within the prototype stage. Item selection was primarily based on a review of the empirical literature on adolescent violence (i.e., through prior reviews, meta-analytic investigations, and individual studies) and the magnitude/robustness of each risk/protective factor’s relationship with violence. While varying degrees of empirical support were found for all items included within the SAVRY, a small number of items were retained despite their lower association with violence due to their perceived clinical relevance (e.g., poor compliance). Moreover, due to the relative lack of empirical research on protective factors in youth at the time of development, the protective factors included within the SAVRY were considered preliminary. This is reflected in the altered rating format of present/absent and the smaller number of protective factors incorporated into the SAVRY relative to the number of risk factors.

The SAVRY has gone through various stages of development and revisions based on preliminary research and feedback from professionals in the field. The various iterations included a pilot version and Consultation Edition. The Consultation Edition was further revised to reflect changes to Item 21 (referred to as Version 1.1). Initially, the SAVRY required administration of the Psychopathy Checklist: Youth Version as part of rating Item 21 (formerly referred to as Psychopathic Traits); however, this requirement was dropped following the initial printing of the Consultation Edition. This was to reduce the risk of negative connotations associated with the term psychopathy and to ensure that rating of the SAVRY was not dependent on the administration of another measure or tool and was in keeping with the intention of the measure to be used by professionals working with adolescents, not necessarily clinicians. Moreover, by revising the item to represent low empathy/remorse, the authors argued that capturing the cluster of traits represented by the item was more important than assessing the clinical construct of psychopathy as a whole. The SAVRY was subsequently published commercially through Psychological Assessment Resources in 2006.

Reliability and Validity of the SAVRY

A strong evidence base exists to support the reliability (i.e., internal consistency and interrater reliability) and validity of the SAVRY within both applied and research settings. Although less of a focus among risk assessment tools, the SAVRY has demonstrated adequate psychometric properties (e.g., internal consistency), while interrater agreement has typically ranged from good to excellent for the risk total score and summary risk rating. With respect to predictive validity, reviews, meta-analytic investigations, and independent studies have found moderate to large effect sizes for the SAVRY in predicting violent, nonviolent, and general (i.e., any) reoffending among adolescent offenders across various follow-up periods; however, results of studies examining the SAVRY’s predictive validity among adolescent male sexual offenders have been mixed. Despite this, researchers have found the predictive validity of the SAVRY to be comparable across age (i.e., 13- to 15-yearolds vs. 16- to 18-year-olds), gender, type of sample/ setting (e.g., specialized school, correctional, forensic/psychiatric, community, and treatment), study type (i.e., prospective/retrospective), and cultural and ethnic background (albeit research is limited in this regard). In addition, the SAVRY has been found to be equally predictive of institutional and community violence and, despite being significantly associated, to add incrementally to the prediction of recidivism relative to other common adolescent risk assessment tools such as the Youth Level of Service/Case Management Inventory. Although the protective factors of the SAVRY are considered underdeveloped relative to the risk factors, the Protective Factors domain has demonstrated negative associations with violence and general antisocial behavior and, in some studies, has been found to add incrementally to the risk domains in predicting reoffending.

Given that approximately two thirds of the SAVRY items are purportedly dynamic in nature, recent research has examined whether the SAVRY could reliably capture change in a sample of adolescent male sexual offenders, all of whom had undergone a residential cognitive behavioral treatment program to reduce risk of sexual offending, and whether the observed change in risk and protective factors was related to changes in offending outcomes. Dynamic items found within the Social/ Contextual and Individual/Clinical Risk Factors and the Protective Factors domains displayed statistically significant changes over the course of treatment with approximately 8.0–38.7% of the sample of 163 youth displaying reliable improvements in risk. However, neither the dynamic change scores nor the presence of reliable change on the SAVRY was significantly associated with reoffending (i.e., any, violent, and sexual) after controlling for baseline scores on the Historical Risk Factors domain. Therefore, while dynamic risk and protective factors incorporated into the SAVRY can reliably capture change over time, further research is required before any firm conclusions can be made regarding the association between change in dynamic risk factors on the SAVRY and reoffending.

Final Thoughts

Empirical evidence has established the SAVRY’s ability to predict violent reoffending, providing strong support for its use when assessing risk of violence in adolescent offenders.

Moreover, with improved resource allocation being observed following implementation of the SAVRY, it may serve as a useful aid when making informed decisions concerning the management of violence risk. To further support this process, in 2014, a risk management toolkit for youth justice professionals that directly maps onto the SAVRY items, referred to as the Adolescent Risk Reduction and Resilient Outcomes Work-Plan (ARROW), was developed. The ARROW was designed to assist in the development of case-management plans by providing evidence-based resources and a structured approach for identifying appropriate risk management strategies aimed at reducing risk factors and bolstering protective factors that have been incorporated into the SAVRY. Although research on the ARROW is limited, the addition of the ARROW to the SAVRY allows for a unique combination that further structures and guides the risk assessment and risk management process.

References:

- Borum, R., Bartel, P., & Forth, A. (2006). Manual for the Structured Assessment of Violence Risk in Youth (SAVRY). Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

- Borum, R., Lodewijks, H., Bartel, P. A., & Forth, A. E. (2010). Structured Assessment of Violence Risk in Youth (SAVRY). In K. Douglas & R. Otto (Eds.), Handbook of violence risk assessment (pp. 63–80). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Olver, M. E., Stockdale, K. C., & Wormith, J. S. (2009). Risk assessment with young offenders: A meta-analysis of three assessment measures. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 36, 329–353. doi:10.1177/0093854809331457

- Singh, J. P., Grann, M., & Fazel, S. (2011). A comparative study of violence risk assessment tools: A systematic review and metaregression analysis of 68 studies involving 25,980 participants. Clinical Psychology Review, 31, 499–513. doi:10.1016/ j.cpr.2010.11.009

- Viljoen, J. L., Brodersen, E., Shaffer, C., Muir, N., & ARROW Advisory Board. (2014). Adolescent Risk Reduction and Resilient Outcomes Work-Plan (ARROW). Burnaby, Canada: Simon Fraser University.

- Viljoen, J. L., Gray, A. L., & Barone, C. (2016). Assessing risk for violence and offending in adolescents. In R. Jackson & R. Roesch (Eds.), Learning forensic assessment: Research and practice (2nd ed., pp. 357–388). New York, NY: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.